Hugh Thomas – Classical Archaeologist

Why do you think archaeology is important?

In order for us to understand who we are today, we need to know where we came from. We have evolved from hunter gathers to astronauts in less than 12,000 years, which is a miniscule time period when you consider the Earth is several billion years old. Each ancient culture from the Greeks to the Mayans have aided in this development in one way or another. As such, we should endeavour to try understand those ancient people and their impact on us today. We can only know who we are today by knowing where we came from.

When did you know you wanted to be an archaeologist, and what was it that made you want to be one?

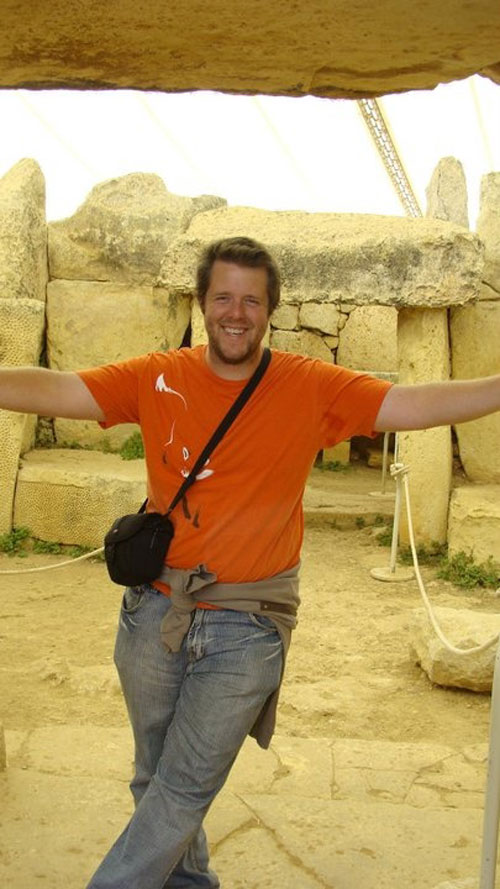

Funnily enough, I never grew up wanting to be an archaeologist. I grew up loving history, astronomy and computers and was always unsure about which field I would like to study at University. In my second year at University, at the suggestion of a friend, I enrolled in an archaeology class. I wasn’t sure I liked it until my first tutorial. As I put on gloves, I was handed a small pot. I had no idea what it was, but was told it was a Mycenaean Stirrup Jar which was over 3200 years old. I was amazed at how beautiful the pot was and just how much information about the Ancient Greeks we could ascertain from one tiny little object. This was the first time I had ever held an archaeological object and from then on I was hooked. I went on my first archaeological project on the small Greek island Kythera, just 3 months later.

What study did you do to become an archaeologist?

I took a variety of Classical Archaeology courses at University, focusing on Greece and South Italy. I also did honours, where I wrote two significant papers, one on shield devices (the images on shields) and another on gesture on Greek art. A year later, in March 2008, I enrolled in a PhD studying gesture on Ancient Greek funerary iconography, which I submitted in August 2012. All up, it has been almost 10 years from when I first became interested in Archaeology until I finished my PhD.

What are some of the key jobs you’ve had?

My very first job was as a DJ at weddings and 21sts. Each Saturday night, I had to go to someone’s party and play music whilst my friends were going out and having fun. I had to wear a very tacky suit and pretend like I loved music and was excited to be there, despite the fact that I hated every minute of it. I quit that job as soon as I returned from my first archaeological project in Greece. I realised that in order to enjoy work I had to do something which made me happy. A few weeks later I started training at the Nicholson Museum where I worked for the next several years.

I then tutored and lectured at the University of Sydney and the University of NSW. I have also created videos which I placed on Youtube, and was eventually employed by several companies to help test video products or review the latest movies.

What skills or capabilities do you think are important to being a good archaeologist?

In my mind there are two really important skills each archaeologist should have. Firstly, you need to be able to interpret data. When you excavate, you need to look at a variety of different types of evidence to be able to understand what’s going on. From the stratigraphy of the site to the artefacts, everything you dig up can assist you in interpreting the history of the site. At the same time, it helps if you have a vivid imagination. I always think the best archaeologists are the ones who had invisible friends when they were younger. Much of the material we dig up is broken or sometimes completely missing. By imaging the objects as complete or reconstructing a building with your imagination, it often helps with your ability to piece together what is happening on the site.

What advice would you give to someone interested in this career?

If you are interested in archaeology, go to museum events or try to volunteer on an excavation either here or overseas. You’ll be amazed at how amazing it is just picking up and experiencing objects that are hundreds or thousands of years old. Also, watch ‘Indiana Jones’ – because if you become an archaeologist 90% of the questions you will get will be about the movies…. And no, I don’t wear an old hat or carry a whip.

How do archaeologists spend their time?

Archaeology isn’t just digging. The vast majority of our time is spent in the library researching or entering data into a database. This would take up most of the year if you are a full time researcher. Excavations usually go on for 4-6 weeks. The rest is research.

What’s it like living in the ‘dig house’ during a dig?

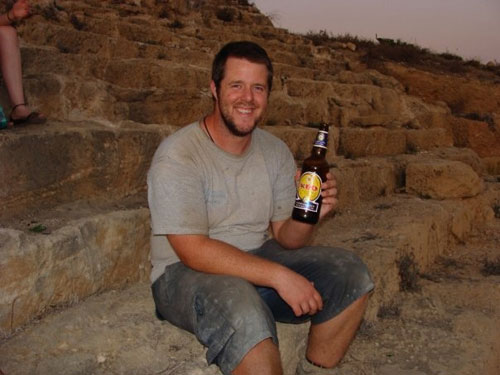

Excavations are great fun although they are physically exhausting. As I am a Classical archaeologist, I have always excavated in Greece and Cyprus. Generally, you wake up very early, around 5-6am. After a quick bite to eat you are usually on site between 6-7am, just after sunrise. The reason for this is that from June-October, it gets very hot during the day, so to fit in a full days excavation it is best to start early and finish early. On some days, I have had to dig in 35+ degrees Celsius, so you don’t want to be outside after 2pm when it gets even hotter. You’ll normally head home around 1-2pm and have lunch. Then you do pottery washing and finds processing. This may take 1-2 hours depending on how much material you have excavated. By 4pm you wind up and have free time which often involves beaches, ice-creams, cold drinks, beer etc. Dinner is around 7ish and then people either hang out, watch movies, sleep.

An excavation is amazing fun. You spend 17 hours a day with people, 7 days a week for 6 weeks, so it allows you to form very close friendships. You will have fun together, laugh and learn but you will also have the odd argument as you would with anyone when you’ve seen them for 30 days in a row. If you go on a 6 week excavation, you’ll normally have the 4th week blues, a week where everyone gets grumpy and crabby. But often the hard and physical life of an archaeologist brings you together and to this day, many of my closest friends are those I have met on excavations.

Which parts of your job do you love, like, not so much….?

My most favourite aspect of archaeology is excavating an object that was last used several thousand years ago, knowing you are the first person to see this object since its last owner either left it somewhere, tossed it away, or had it buried with them.

The part I hate about archaeology is sunscreen. When you are working day after day in 30+ degree heat, you need to be careful with sun protection. You need a hat, sunglasses and of course, sunscreen. Generally, I’ll put on sunscreen three times a day as you can sweat it off quite easily. That means over the course of a normal excavation you will put on sunscreen well over 100 times. Eventually the smell and feel of it just annoys the hell out of me. Also spiders…. Giant spiders…

How do you and your family cope with separation during archaeological digs?

When I first started going on archaeological projects, it was difficult to make contact with family and loved ones. Many of the small Greek islands had very slow internet, skype didn’t exist and SMS costs you huge amounts of money. Now days Skype, facebook, emails, sms, video phone calls all help with home sickness as at least you can see each other. That being said, by the time the next excavation rolls around I am so sick of my family the thought of several weeks away from them fills me with happiness!

What’s been your worst experience in archaeology?

On an excavation in 2005 I was riding a scooter on a quiet back road of the Greek island of Chios, when a truck veered towards me forcing me off the road and causing me to crash onto gravel. I ended up with bad grazes and a badly hurt ankle that had me in a cast for a week. Although I could still help out by washing pottery, it was hard seeing my friends go off to site and excavate amazing objects whilst I sat in a small shed and washed pottery by myself. Also wearing a leg cast in 30 degree heat means you start to smell… bad!

What’s been your best experience in archaeology?

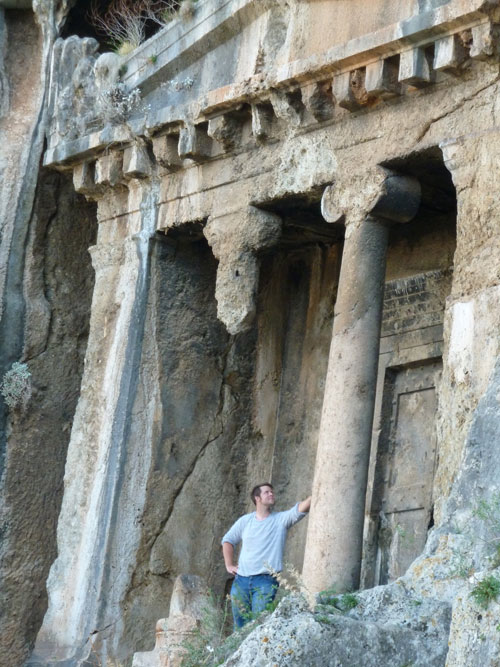

I have always loved ancient architecture. I loved the elaborate sculptures that adorned them and the amazing detail they put into decorating each building. Several years ago I was digging on at the University of Sydney’s excavation of a Hellenistic/Roman theatre in Paphos, Cyprus. Two or three days into digging, we were about to wrap up for breakfast when I looked down at a small stone. It had an unusual shape to it that didn’t look natural. I knelt down and started troweling away the nearby dirt. The stone wasn’t small at all but seemed to be getting bigger and bigger as I cleared more dirt away. I remember when I realised this wasn’t just any old rock, but instead was a Corinthian Capital, the large decorative stone that sat atop a column in a building. Over the next day or two, I got to excavate the capital, which wasn’t small at all but was several hundred kilograms of beautifully carved marble. Although archaeology is a group effort, it is always nice to be the one to discover such an amazing object.

What’s your realistic and/or dream hope of archaeological achievement?

I love teaching. So ultimately, I’d love to have a lecturing/research position at a university and perhaps run a little excavation of my own.

What are some words you would use to describe your experiences as an archaeologist?

Amazing, thought-provoking, interesting, puzzling, infuriating

Is there anything else you would like to share with our readers?

Don’t ask an archaeologist if they dig up dinosaur bones…