Melanie Pitkin – Egyptologist, Museum Curator and Tour Leader

Why do you think archaeology is important?

Archaeology provides us with the tangible evidence we need to help reconstruct the past. It can tell us so much – from how old something is, to filling in gaps in historical narratives, solving long lost mysteries and bringing us closer to the lives of people who existed before us. Archaeology works alongside written sources and oral histories, when they are available, to help extend our informed knowledge and validate (or disprove) theories. As a discipline, archaeology has also evolved a great deal in the last century – from an era of treasure hunting and exploration to rigorous scientific enquiry. This means that, today, archaeology offers us whole new levels of importance in non-invasive surveying techniques like ground penetrating radar, remote sensing and advanced methods of aerial photography, as well as professional standards in ethical practice such as the handling of sensitive material like human remains.

When did you know you wanted to be an archaeologist, and what was it that made you want to be one?

While moving house a few years ago, I came across a diary I kept as a primary school student which said “one day I’m going to be an archaeologist”. It actually really surprised me – not simply for the fact I managed to spell archaeologist correctly, but that I had no recollection of ever thinking or writing this at such a young age. In fact, I went through a stage in my early teens of wanting to be a graphic designer, and then a professional tennis player (although that was a short-lived dream!). It wasn’t until I was in Year 11, as a 15/16 year old, that my high school Ancient History teacher both noticed and nurtured my passion for archaeology and ancient history, especially Egyptian, and it was then I consciously recall that I was going to make it my lifelong pursuit. I’d say my interest in archaeology, however, stems from my travels. My first overseas trip, as an eight year old, was to the UK – we spent two months visiting every museum, heritage and historic site you could possibly imagine, and I absolutely loved it! I’ve also always been drawn to the Middle East, so it seems quite likely that my specific interests in Egyptology came as a natural extension of that.

What study did you do to become an archaeologist?

In any form of research, you never really stop studying! Straight out of school I enrolled in a Bachelor of Ancient History degree at Macquarie University. From the outset I knew I wanted to major in Egyptology, so undertook subjects in Egyptian hieroglyphs, art, history, architecture, archaeology and religion. I also studied French and German reading courses, Latin and introductory subjects to Roman and Greek history. At the end of my third year I was selected to take part in a dig in Egypt with the Macquarie University team (this counted as a subject) and was undeniably one of the best experiences I’ve ever had. Upon returning, I enrolled in the honours program, which included a 10,000 word thesis (my topic was the chronology and dating of the viziers, or high officials, of a king called Unis from the Old Kingdom*) and coursework subjects in historiography and Egyptian history. After this degree, I actually applied and was accepted for a PhD in Egyptology, but I personally felt a little unsettled about career prospects, especially since by that time I knew I wanted to work with archaeological collections in a museum. So, I completed a Masters degree in Museum Studies at the University of Sydney (integrating Egyptology wherever possible) over 1.5 years while working full-time at the Powerhouse Museum. Then, in 2008, I went back to Macquarie University to study for my PhD in Egyptology – where I still am, while working full-time, and will continue to be until about 2015! My thesis topic is on the typological dating of false doors** and funerary stelae of the First Intermediate Period.

How long have you been an archaeologist?

I’ve been formally studying in the field of archaeology since 2002. My first archaeological dig was in 2005 and I commenced full-time professional museum work in late 2006.

What are some of the key jobs you’ve had?

I’ve worked as a museum curator (current position), a museum evaluation and audience research officer, a museum registrar, a cataloguer for an archival film and stock footage company and a research assistant at the Australian Centre for Egyptology. In the last couple of years, I’ve also been doing some extra casual work – tour leading to Egypt and providing research assistance to university Professors.

What skills or capabilities do you think are important to being a good archaeologist?

First and foremost, passion. If you’re passionate about your subject matter, then all the other qualities you need to be a good detective will follow (after all, that’s what archaeological work is all about – piecing together parts of a puzzle to try and solve a problem). You need to be very methodical, patient and have a high attention to detail. You also need to know how to interpret and research evidence. Beyond the fieldwork, being an archaeologist involves seeing how everything fits together into its historical context and communicating this effectively. It’s an archaeologist’s responsibility to then write up, publish and present their findings, sooner rather than later, to the benefit of the broader research community and public.

What advice would you give to someone interested in this career?

Be persistent. You’ll hear people around you question your intentions, especially as archaeology is not considered to be the most lucrative of careers. However, there are many different pathways where you can incorporate archaeology – like museum work, teaching, university lecturing and tour leading. Archaeological digs also require many different experts – architects, human remains experts, scientists, illustrators, ceramicists and photographers. So, it is possible to fuse a career in archaeology with another seemingly different skill or interest you may have. There are also many opportunities to volunteer on digs and I would recommend this to any budding archaeologist, as the earlier you start to get practical experience, the better.

How do archaeologists spend their time?

As I am early in my career and still studying for my PhD, my time is somewhat split. By day, as a museum curator, I spend a lot of time researching, writing and developing ideas for exhibitions, the web, public programs and so forth. This is either done at my computer, in our research library or our collections storage area. For my PhD, it’s not too dissimilar. At the moment, most of my time is spent translating hieroglyphs, reading, trying to keep track of all my thoughts, mapping out my data sets for analysis, liaising with my supervisors and housekeeping (i.e. recording my bibliographic references in Endnote, maintaining my hard copy files etc.). I also travel overseas for my research annually, especially to Egypt and the UK, visiting other museum collections with objects relevant to my study, attending conferences, meeting other researchers and so on.

Fieldwork is not central to the completion of my PhD, but an added bonus. I will be working at Tell el-Amarna (the very important site of King Akhenaten of the 18th Dynasty – which, in fact, post dates my thesis topic by about 800 years) between September and December 2012 with Cambridge University’s excavations there. Instead of using my recreation leave to relax on the beach, like normal people, I will be excavating human remains and cataloguing ancient finds!

What’s it like living in the ‘dig house’ during a dig?

The ‘dig houses’ I’ve stayed at in Egypt, to date, are actually hotels, but not the type you may be thinking of! They are pretty basic – with a communal bedroom, bathroom and eating area (fortunately with a cook and waiter on hand!). We work 6 days per week, Sunday – Thursday (for Muslims, Friday is the holiest day of the week, so this is our day off) and we start very early, leaving the ‘dig house’ before sunrise.

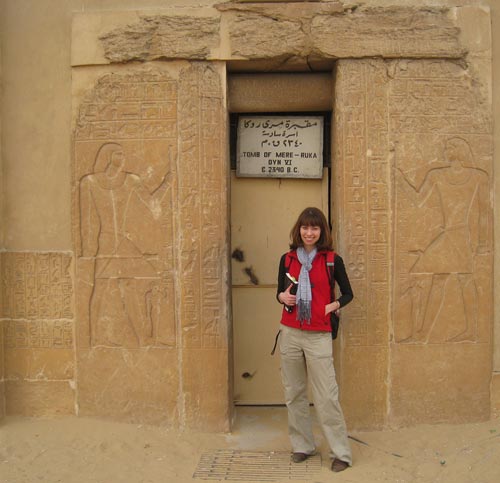

When I worked with the Macquarie University team at Saqqara (about 30kms south from Cairo), all the digging was done by the local Egyptian workmen who were overseen by our Director or Assistant Director. The rest of the dig team is divided up for various tasks which span epigraphic work (recording the tomb by means of tracing the inscriptions and wall scenes onto large sheets of mylar), finds drawing and processing, photography, drawing architectural plans and conservation work. The digging day ends between 3 – 4pm at which point we return to our ‘dig house’ to refresh (i.e. rid ourselves of all the sand!), have dinner and catch up on emails/correspondence. This time is also used by the team’s illustrator to ink the wall scenes and inscriptions from the tomb(s) onto tracing paper and write up various administrative reports for the Ministry of Antiquities. Our one day off a week is a real luxury. It’s a chance to try (!) and sleep in and explore the local area. Two of my regular, favourite places to visit are the Khan el-Khalili markets and the Egyptian Museum. We might also meet up with other archaeological teams or attend a special function – like a performance at the Cairo Opera House.

Which parts of your job do you love, like, not so much…?

I always find the early starts a bit of a challenge and I’m not the biggest fan of communal bathrooms (especially when the locks don’t work on the doors!). However, I will endure anything when I know I’ll have the opportunity to do what I absolutely love – which is being in Egypt and helping to improve our understanding of Egypt’s rich past through fieldwork, research and interpretation.

How do you and your family cope with separation during archaeological digs?

Lots of emails and text messages!

What’s been your worst experience in archaeology?

Being ill on site is a pretty terrible experience, especially when you’re up a remote mountain in Middle Egypt. But, as I hear, it’s a rite of passage for any archaeologist (especially in Egypt) to fall victim to something at some stage – whether it’s the food, water, pollution, sand etc. If nothing else, it will build up your immune system and make you a stronger person (well, I can say that while I’m feeling fit and healthy!).

What’s been your best experience in archaeology?

Being a part of Macquarie University’s 2005 discovery of three Late Period mummies at Saqqara. Zahi Hawass described them as among the best preserved mummies ever found as they were covered in full-length intricate faience beaded nets which were brightly coloured and impressively intact. There is a photo in this ABC story about it. It was the most incredible experience to be part of the whole process – from their initial discovery all the way through to the opening of the coffins and their cleaning and conservation. In fact, the cleaning and conservation part was something which will stay with me forever. The Director of the expedition, Professor Kanawati, and I used a camera puffer and tweezers to delicately remove the sand from between the very fine beadwork from one of the mummies. It took several days. You had to be so patient and so careful; it was very easy for the beadwork to move if you pressed on the puffer with too much force. The mummy bandages and thread which kept the beads together were also extremely fragile. It was painstaking work – lots of crawling around, intense concentration and moments where you’d forget to breathe, but so very worthwhile.

What’s your realistic and/or dream hope of archaeological achievement?

It doesn’t have to be by me, but given the nature of my PhD, one of my hopes is for the discovery of the administrative centre of the Herakleopolitan kings (these were the rulers of Egypt’s 9th and 10th Dynasties). Although the Spanish team have been excavating at modern day Ihnasya el-Medina, close to the Faiyum, since the 1960s and have discovered a number of Herakleopolitan dated false doors, they are yet to reach any conclusive evidence that this is actually where they had their capital.

There are many other archaeological dreams I have related to the First Intermediate Period, as this is perhaps the ‘foggiest’ period of Egyptian history, but more broadly speaking, it would also be wonderful to discover Alexander the Great’s tomb, and the burial place of Antony and Cleopatra (Kathleen Martinez, a Dominican archaeologist, has been searching for the latter for a number of years at a site called Taposiris Magne in the Delta. You can read more about this here: http://www.enbuscadecleopatra.com/en/).

What are some words you would use to describe your experiences as an archaeologist?

Intrepid, surreal, stimulating, gruelling, awe-inspiring, tiring and enlightening. I could keep going!

Is there anything else you would like to share with our readers?

Surround yourself by other passionate students, researchers and academics early on. These are the people who will really drive you, cultivate your interests and teach you an enormous amount. I’ve been fortunate to have a few wonderful mentors who have helped to make and enhance every aspect of my archaeological journey – but, it never stops. You never stop learning and meeting amazing people, so always be open and willing to learn from the knowledge and life experiences of others.

*The dates provided here are after Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson, ‘The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt’, (Cairo, 2002) pp. 310-312:

Old Kingdom (Dynasties 3-6, c. 2686-2181 BCE)

First Intermediate Period (Dynasties 7-early 11, c. 2181-2055 BCE)

Dynasties 9-10 (2160-2025 BCE)

Dynasty 18 – Akhenaten’s reign (1352-1336 BCE)

** False doors are blocks of inscribed stone, or wood, typically placed in the west wall of the tomb’s chapel. The name ‘false’ comes from the fact that it looks like a door but you can’t walk through it. Instead, they served as the symbolic link between the realm of the living and the realm of the dead. The ba (or soul) of the deceased would magically pass through the false door into the afterlife. It was also the place at which visitors would come to the tomb, recite the name of the owner and his/her achievements in life and leave offerings.

Stelae replaced false doors in the First Intermediate Period. These were just ordinary slabs of stone – not shaped like a door nor with its elaborate architectural features but which still had the same purpose.