by Irma Havlicek

Powerhouse Museum Online Producer

The geophysical work that will underpin the excavation work at Zagora

Now to the geophysical work which is the reason for the hard yakka (for those outside of Australia, ‘hard yakka’ means ‘hard work’) of site clearing I wrote about in an earlier post.

The main aims of this first phase of the Zagora Archaeological Project are to use the best technology available now, firstly, to try to give us a general overview of the layout of the whole site before we start excavating. And, secondly, also to determine where archaeological excavation is most likely to produce the best evidence about life in Zagora during the time of the settlement – from about 900 – 700 BCE.

The best techniques now available are those of archaeological surface survey (more about that later) and of geophysics – the study of the physics of the Earth. Over 3000 years, earth, stones and plants have covered the remains of the Zagora settlement. So what we are seeking is below the surface of what is visible above ground.

The geophysical survey team

The Zagora Archaeological Project has contracted geophysicist, Dr Apostolos Sarris, from the Institute for Mediterranean Studies, Foundation of Research & Technology, Hellas, Rethymnon, with his team: Dr Nikos Papadopoulos, another geophysicist, and two archaeologists, Dr Gianluca Cantoro and Sylviane Dederix. This unit is based in Crete but their work takes them around the world. Recent projects apart from Zagora have been in Hungary, Cyprus, Egypt and other sites in Greece. Apostolos and Nikos are Greek, Gianluca is Italian, and Sylviane is Belgian. Geophysics, like archaeology, is a truly international activity.

I found it fascinating to discover that Apostolos had been a particle astrophysicist – examining the physics of the stars. He fell in love with a woman who is an archaeologist, and this inspired him to change his career from a study of the stars to a study of the Earth.

The geophysical process

The geophysical work takes place on carefully measured grids, marked out by tape measures in rectangles. In the case of the Ground Penetrating Radar analysis, which requires a machine to be rolled over the surface [see below], sometimes they have to work around thick bushes or stone piles which the machine cannot go over, so the full rectangular shape cannot be surveyed; though I was amazed at how far up the stone piles they did manage to push the machine – a heroic effort.

Usually, though, they try to work grids that do not include stones or plants, if this is possible. Their measurements take place along the X-Y axis at half metre intervals across the grid. Two people are required to move a tape a metre at a time along the grid, so the person holding the instrument can walk in straight lines, first along the tape, then half a metre along from the tape, from one end of the grid to the other. Then the tape is moved further along again. This means that if the grid is 20 metres by 10 metres, the person must walk the grid across the 10 metres 80 times – 40 times in one direction with the instrument making the readings, and then also carrying or pushing the instrument back to the start line, to start a new line of measurement. This is quite difficult to explain clearly in writing. I will try to add a video to the blog which will show the process more clearly. The photo, below, shows two of the tapes set out a metre apart.

For the Zagora project, the geophysical team members have been working with four different instruments:

Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR)

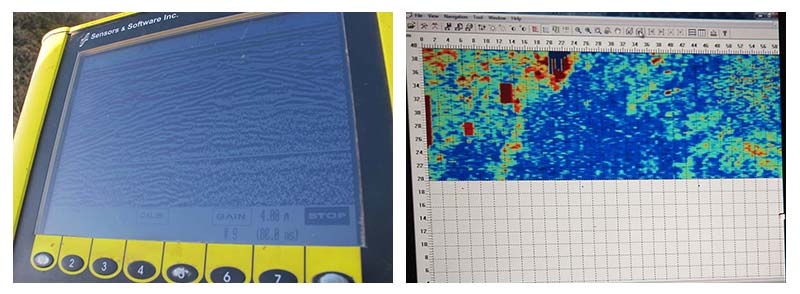

The Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) looks a bit like a lawn-mower and is pushed over the surface of the earth to interpret, through radar, what is the density of the material below the surface of the earth to a depth of two-and-a-half to three metres.

It is to enable effective operation of this machine that the site has to be cleared of rocks and plants to be as level as possible.

The operation (heavy duty pushing!) of this device is very physically demanding. It has to be pushed up and back every half a metre across each grid over difficult terrain. Even though we cleared many of the large rocks and much of the bush and grasses over many areas, many rocks and tufts of grasses remained, and the device had to be pushed over these.

Differential magnetometer also known as a gradiometer

The differential magnetometer, or gradiometer, is the device (pictured at right) that is carried by the operator along the grid lines. The instrument is very sensitive to any kind of metal, so the operator must not be wearing any metal whatsoever. This means they cannot have zips in their clothes, or metal clasps in their shoes. Any metal must be at least two metres away or it could interfere with the magnetic reading they seek from the soil subsurface. This is why I did my photography from quite a distance from the instrument – to ensure I did nothing to interfere with the magnetic reading.

The instrument sends a magnetic pulse down into the ground and records the response picked up from the earth which indicates what kind of magnetic field is detected by the device; in other words, it measures the variations in the magnetic field beneath the surface of the earth to a depth of about two metres. If the magnetic field is strong, it may indicate a large human-made object – or it may just be a large rock.

Resistivity or resistance meter

The resistance meter measures the resistivity of the ground which varies according to the physical properties of subsurface materials in terms of how electrically conductive or resistive they are. The device measures to a depth of about one to two metres.

The two prongs of this device have to be lifted out of the ground every step the operator takes, and then pushed into the ground again (this requires force, pushing down with the operator’s foot). They have to do this in the same direction (carrying the device back the other way), every half metre, along each grid that is surveyed. You can see the guide lines, set down in tape every metre, in the photo at right.

Electromagnetic instrument

The electromagnetic instrument’s active sensor has two antennas, one antenna transmits an electromagnetic impulse up to four metres into the ground, the other one receives the signal back. A signal is returned to the device when the electromagnetic impulse hits hard material other than soil (could be rocks or could be building or wall structure).

The signature of the receiving signal depends on the electrical and magnetic properties of the subsoil, in other words, this device measures electrical conductivity and magnetic resistivity.

Apostolos climbed through and over thorny bushes (unable to wear heavy duty protective boots which would have had metal in them) to get the best possible results – true dedication.

What they are looking for

What they are looking for are anomalies – or patterns which look different from what you would expect to see in the earth. For example, shapes such as rectangles which indicate human activity rather than natural formations, or very large shapes – which could indicate a kiln, for example, or just a large rock.

It takes years of training and an experienced eye to read the visual representations produced by this data, and Apostolos is a world expert in this field – so we are very fortunate to have him on this project.

There is no guarantee that what appears to be an anomaly will turn out to have been the result of human activity. But using up to four different devices over the same grids enables the comparison of results over the same areas – and if the anomalies appear in the result of each machine, that provides a stronger indication that the anomaly is likely worth investigating.

Thank you geophysical team

I started this post talking about hard yakka – the geophysical team worked every day since they got here – including Sunday – nine days straight. The results of their work will have a huge impact on where excavations will take place. But to gather those results, they have had to work hard, physically, first laying grid lines, and then repeatedly walking up and down the grid lines carrying or pushing various machines – from about 8am to about 2pm or 3pm most days – to get the data to provide the results the Zagora team needs. They have worked (as have the archaeologists in the Zagora team) in temperatures into the 30s, pouring rain, thunderstorms and fierce relentless wind. Not only that – but after their hard days in the field, they went back to their accommodation and spent hours reviewing the data they had recorded each day. Thank you Apostolos, Nikos, Silviane and Gianluca.

5 thoughts on “Let’s get geophysical”

It’s so great to be able to follow every stage of the dig from the land clearing and geophysical radar to having a good night out enjoying some dancing and local culture. Every day is so interesting and it’s fabulous to be able to have such a close view of all the activities. Can almost beleive I’m with you. Thanks so much.

So glad you’re enjoying it; it is a privilege to be here and to share it with a wider audience.

Hi again Irma – this a great insight into the work of the Geophysical team and what it really takes to conduct a dig! However I have to say that in all your photos the sun is shining!

Great work. Guide line for young archaeologists.Congrats.

Thank you – I do hope we provide something useful for young archaeologists and also maybe inspire younger students to consider archaeology as a hugely fulfilling career.