by Irma Havlicek

Powerhouse Museum web producer

Kristen Mann was Trench Supervisor of Excavation Area 4 in 2013 and will be again this year. Kristen is doing PhD research, the main thrust of which relates to ‘spatial patterning of behaviour’ – that is, how the layout of buildings, rooms, spaces in and between buildings, pathways, communal spaces, etc. influences people’s behaviour.

Kristen is interrogating the layout and configuration of spaces at Zagora to try to understand how people lived there three thousand years ago, and to determine how archaeologists may be able to interpret behaviour from household arrangements.

Kristen is interested in access and use of space, and how people moved through and around the buildings and the settlement.

Seeking answers

Kristen is seeking answers to many questions. What can we deduce about their society and lifestyle by the way they used the spaces inside the buildings and around the settlement?

There was only one external door in the buildings excavated in the 1960s and 70s. Which way did doors face, and what reasons might there be for this? How did the layout of buildings influence access inside buildings, between buildings, through the settlement and into and out of the settlement?

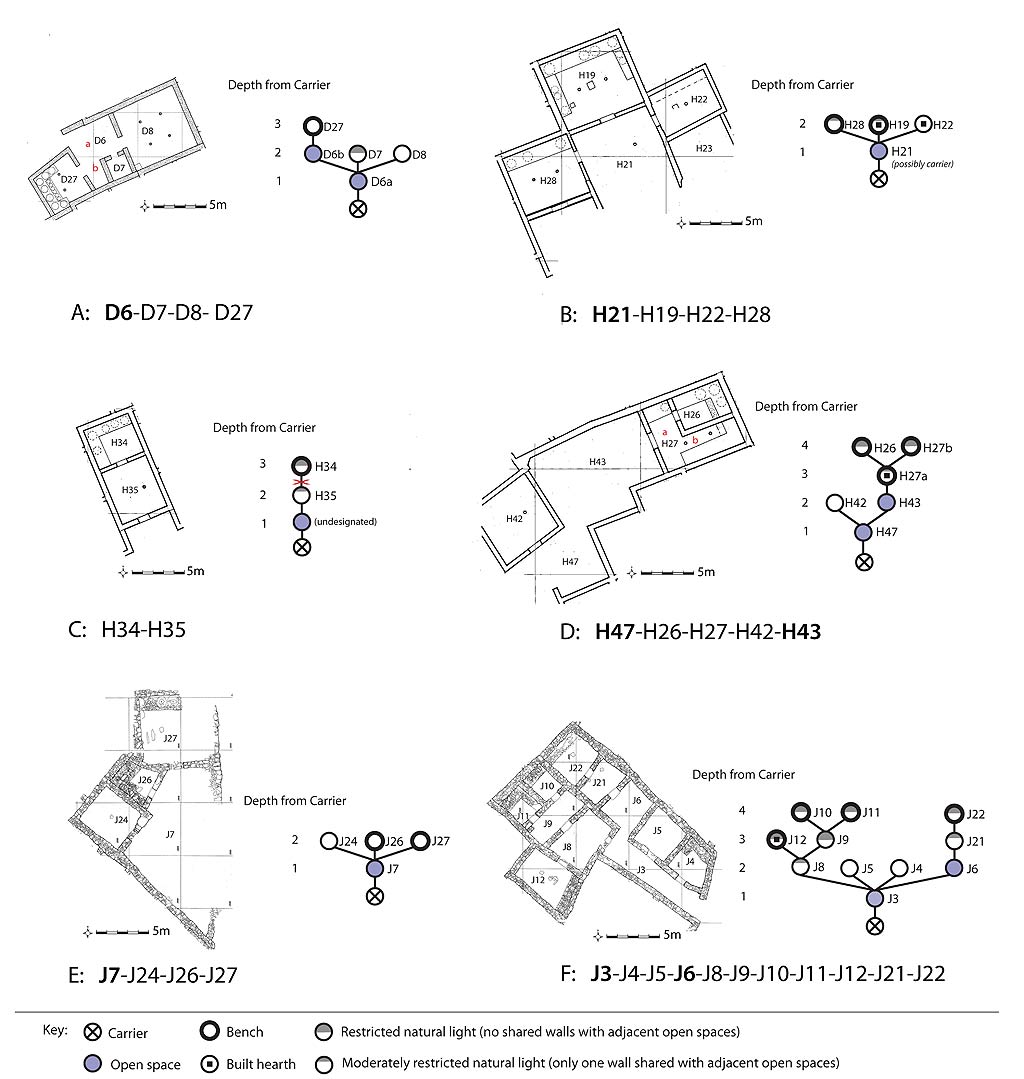

What were the arrangements of spaces among and between rooms? For example, in some cases it appears that entry into a building was through a door into one room, which then had an entry door into a second room, which then had an entry door into a third room that appeared to have no windows. (We can’t be sure about the absence of windows because rarely is the full height of a collapsed wall preserved and the little evidence that we do possess suggests that windows could be placed high in a wall.) What benefit might there have been from this kind of room arrangement? Might the dark, innermost room have been for storage of valuable or perishable material or food? Or might entry to the innermost room have been permitted only to some members of the household and not others? If so, on what basis might this exclusive access have been granted, and what does this indicate about Zagora society?

What would the presence or absence – documented or inferred – of windows indicate? What might be interpreted from the number, shape, size and positioning of windows? What influence does light or darkness have on potential uses of a room? What does the presence, size, number and positioning of benches, hearths, pots and other artefacts indicate about the usage of the buildings and the site?

What activities, such as farming, textile production (spinning and weaving), storage, food processing, metalworking, etc., are suggested by spacial configurations and by the artefacts (such as metalworking waste or tools used in spinning or weaving) found in and around different households? What was the scale of these activities, and what is their spread and concentration across the settlement? Does the evidence suggest that food and textile processing and manufacture or metalwork was undertaken for the use of the Zagora population only, or does it appear that there may have been trade in these goods?

What were the similarities and differences in household production* across the site? How would these activities have influenced daily life in Zagora? What might investigations along these lines indicate to help better understand the ancient society and economy of Zagora? Do the answers to these questions provide evidence of social differentiation across the site and, if so, in what way?

Zagora is an extensive settlement site with many buildings already excavated (and many more yet to be revealed). The main focus of research regarding significance of domestic architecture in the 1960s and 70s related to whether there was a correlation between the size of rooms and the status of those who lived there. Archaeologists working at Zagora are profoundly aware that the work they are able to achieve now is firmly based on the foundation of the work done in the 1960s and 70s under the direction of Professor Alexander Cambitoglou.

Kristen is using techniques and technologies not available forty years ago to seek and interpret evidence in different ways. The development of database capabilities in recent years enables more efficient and different kinds of enquiries to be undertaken. Work which would have required laborious manual searching through dozens of notebooks and may have taken months to collate forty years ago can now be accomplished in a matter of hours through the Heurist database (developed by Arts eResearch at the University of Sydney; the archaeological interface having been determined largely by Beatrice McLoughlin, Matthew McCallum and Andrew Wilson).

We are all looking forward to further excavations at Zagora in 2014 and the the eventual publication of Kristen’s findings – which will do much to illuminate our understanding of life in the Zagora settlement 3000 years ago.

Many thanks to Kristen Mann who gave generously of her time and expertise in the development of this post.

* The Zagora Archaeological Project will also pick up an evidence that may indicate production processes at a greater scale than the domestic but the focus of Kristen’s work rests on the domestic level.