Web content producer

At the end of every day of excavation at Zagora, whatever artefacts are found (mostly sherds remaining from pottery objects which have broken under roof and wall collapses) are taken to the Archaeological Museum in Chora. There, they are safely stored until they can be cleaned, assessed, sorted, catalogued and, in some cases, repaired.

It’s an important, time-consuming and painstaking job requiring several people’s work every day.

Dr Stavros Paspalas, one of the Zagora Archaeological Project (ZAP) directors and also the project’s fineware expert, and Beatrice McLoughlin, Finds Manager and the project’s coarseware expert, both spend many of their Andros working days at the Museum.

Initial washing of artefacts

The labour-intensive initial cleaning of artefacts takes place in the small rear yard of the museum. This work is done by Stavros, Beatrice and a team of assistants from among the ZAP archaeologists and archaeology student volunteers. Some of the assistants, such as this year, Annette Dukes, specialise in the cleaning work at the Museum rather than excavating at Zagora. Other ZAP team members excavate at Zagora most days and help out at the Museum for one or more days during their time on the project. The ZAP directors believe it is important for all participants, particularly for archaeology students, to participate in artefact cleaning and sorting at the Museum as well as excavating at Zagora to gain a comprehensive overview of the project.

Who works where each day, including how they get there and how they get back to the accommodation is another element of logistics that has to be dealt with daily. Factors which may influence how work is apportioned include whether a vehicle is needed for another purpose, for example, collecting someone from the ferry at Gavrio, or if someone requires some physical recovery time from excavating, and may benefit from a day or two doing less physically demanding work in the Museum rather than on site at Zagora.

Artefacts (mostly ceramic sherds) are taken from Zagora to Andros Museum at the end of every excavation day. They are placed into buckets of water and left to soak to soften the dirt that is stuck to them until they can be cleaned. Then each piece is taken out, one-by-one, and wiped with a wet sponge to try to clear away the caked on mud.

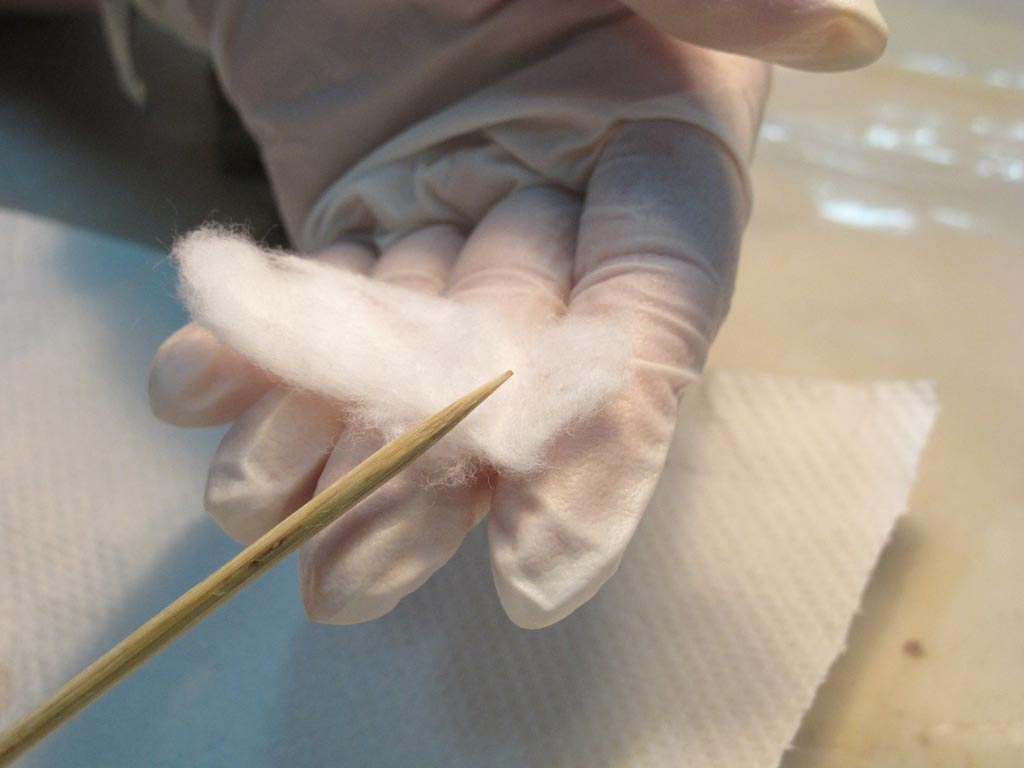

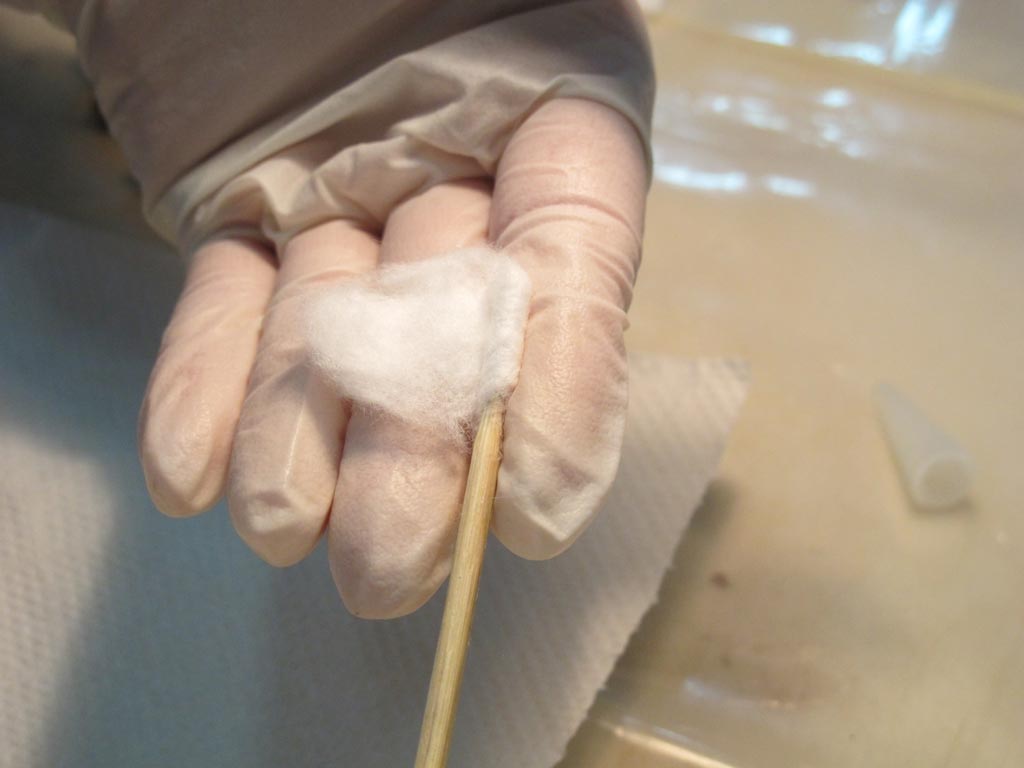

If the mud is sticking really hard, a soft toothbrush may be used or the flat side of a wooden skewer to gently loosen the dirt. Only the flat side and not the pointy tip of the wooden skewer is used to ensure that the ceramic surface, and especially any painted or applied decoration, is not damaged.

After the finds are washed, some of what had been thought to be ceramic sherds are revealed to actually be ‘tricky rock’ – which is rock which looks like a piece of ceramic. It can be hard to tell the difference when the material is caked in earth.

If something notable is found – for example an interesting diagnostic piece, or something with paint or other embellishment on it, it is shown to Stavros or Beatrice for consideration.

It is remarkable how removing dirt from the artefacts using water and these simple tools enables the pieces to come alive before your eyes. And it’s really exciting when anything is found with applied embellishments or paint, even if it is on a sherd the size of a small coin. This is probably so because, unless you have a trained eye, as the experienced archaeologists do, it is difficult to imagine clearly what a small sherd would have been part of. But when you see some paint, you can immediately connect with it – you recognise line, pattern, form (e.g. animal), and you can imagine someone having held that object with a small paintbrush/reed in hand, making those marks. Also the paintwork or applied decoration helps you to consolidate your understanding of the period by helping you to build a mental framework of the kinds of geometric patterns that were common and, so, unified the period stylistically.

The conservation process

We cannot show actual artefacts being conserved – they need to be researched and published in reputable, peer-reviewed, academic publications before I can publish them here. But I can give you a good idea of the process using small stones which are similar in size and colour to many of the sherds which have been found at Zagora.

After the initial cleaning has been done, and the artefacts air-dried, they are sorted into fineware material for Stavros to inspect or coarseware material for Beatrice to inspect. Of course, everything remains in labelled containers throughout, documenting where and when the artefacts were found.

Stavros and Beatrice then consult with Wendy about which artefacts are significant and are to receive further cleaning and conservation treatment. Among factors which would make a piece significant are:

– diagnostic piece, such as handle, which gives a good indication of what kind of object it was part of

– applied embellishment

– painted embellishment

– piece which fits with another piece or pieces to form all or part of an object.

Stavros and Beatrice have such a developed understanding of their respective specialties of fineware and coarseware, that they will often identify a piece of ceramic as belonging with another one even if the pieces were found in different locations and/or on different days. They assess the material by sight and by feel. How thick or thin is the ceramic? What is the shape? What is the colour? How smooth or rough is it? If it is rough, what are the aggregate materials (for example, sand) that were used to make the clay?

Wendy generally wears latex gloves for her conservation work. Our hands contain oils and acids which can cause deterioration in artefact material over time, so wearing gloves protects the artefacts. It isn’t essential to wear gloves when working with ceramics but it is essential when working with metals which are more likely to suffer damage from oils and acids in skin. The gloves also protect the conservator’s hands from the chemicals used and the prolonged handling of ceramic material which dries the skin.

Wendy uses cotton buds (which she makes herself, as pictured) dipped in distilled water to clean any residual dirt from the delicate objects. Sherds which are not identified as part of an object which can be reconstructed are stored away.

Reconstructing artefacts

If many, or even all, fragments of any artefacts have been identified by Stavros and Beatrice, it is a priority for the objects to be reconstructed by Wendy so that the artefacts can be:

– studied

– illustrated

– photographed and

– displayed in a museum

This enables both scholars and the general public to understanding the period better.

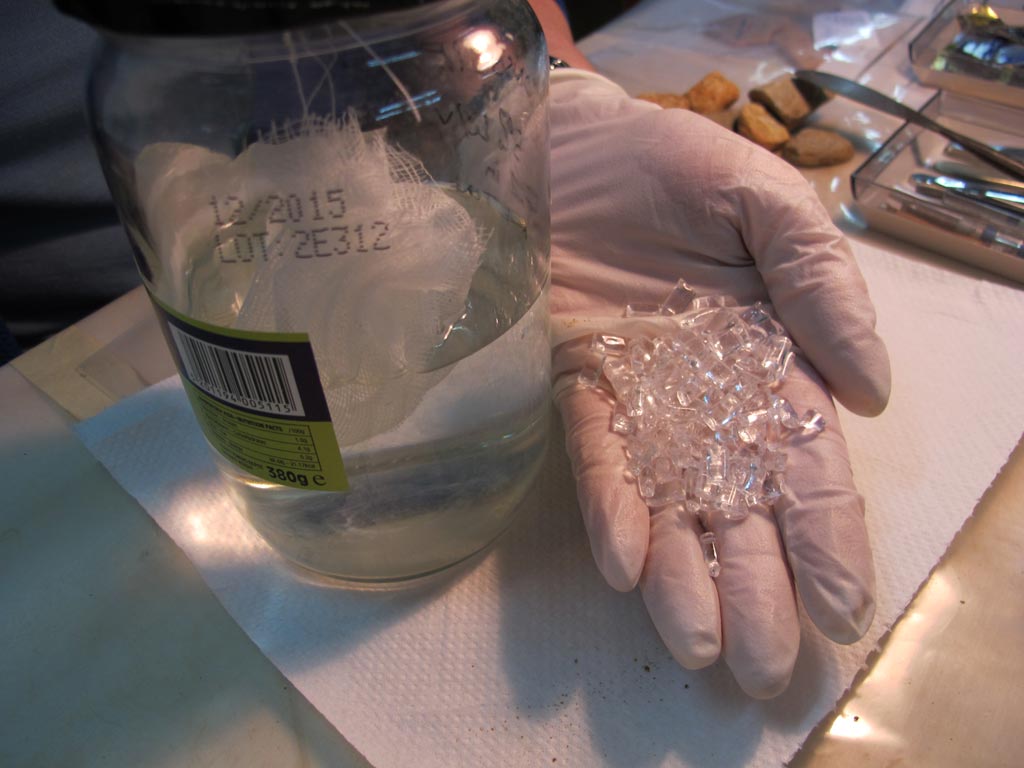

Wendy glues together any sherds which have been identified as belonging together. She mixes her own adhesive, using adhesive resin (Paraloid B72) beads which she mixes with acetone to dissolve the beads into a liquid adhesive. Acetone is the ideal agent because it dissolves the beads but also because it evaporates quickly, leaving no residue. It is important to work in a well-ventilated area because acetone is toxic if inhaled.

Wendy uses a conservation quality adhesive which:

– doesn’t harm the ceramic

– doesn’t yellow with age

– can be removed by being dissolved with acetone.

It is vital for the adhesion to be reversible – you must be able to undo a join in the future if required for further research or because there have been advances in conservation or diagnostic techniques which can be applied to the dismantled pieces.

Wendy carefully weighs the resin beads and the acetone to determine the strength of adhesive required for different purposes. For example a very large, heavy ceramic vessel requires a very strong adhesive to hold the pieces together.

Glueing large pieces together is a slow and arduous process. You can only glue two pieces together at a time. You must hold the two heavy pieces together firmly for several minutes, and then very carefully place the object into a sand tray, with the sand shaped to support the object and assist the adhesive to work to its maximum hold. Wendy also applies masking tape over the joins to assist in the binding process.

Wendy continues to glue fragments to each other until she can reconstruct the original form of the object. It is physically demanding work in the case of heavy, large objects.

When the reconstruction is complete, Wendy uses her cotton buds dipped in acetone to remove any excess adhesive that is visible on the surface of the artefact.

Using adhesive to protect objects

As well as the strong adhesive used for reconstructing artefacts, Wendy mixes a weak adhesive solution which she applies over the surface of soft or crumbling artefacts to strengthen them and prevent crumbling and deterioration. Adhesive used in this way is called a consolidant.

This is done, for example, with pottery which has been fired at low temperatures (called ‘low-fired’) which isn’t hard like china/porcelain but is soft like terracotta pots. It is important to work gently with such fragile material.

Applying consolidant also prevents paint from flaking from the surface of objects.

Thanks

Sincere thanks to Wendy Reade who generously provided her time and expertise in helping me to prepare this post.

2 thoughts on “Cleaning and conserving Zagora artefacts”

What a fantastic post providing insight into conservation techniques for archaeological material. Does Wendy work predominantly by herself at Andros Museum throughout the season?

Hi Vanessa – thanks for your kind comment. The two ZAP stalwarts are our ZAP director and fine ware specialist, Stavros Paspalas, and finds manager and coarse ware specialist, Beatrice McLoughlin. They are at the Andros Archaeological Museum most Tuesdays to Saturdays. (The museum is closed on Mondays. On Mondays they usually either go to Zagora or work on their computers at Batsi.) Annette Dukes, finds assistant, is usually at the museum Tuesdays to Saturdays also. Most days one or two ZAP archaeologists are also at the museum washing finds – mostly ceramic sherds but also bits of bone and other finds. The ZAP directors try to ensure that all the archaeologists who usually excavate at Zagora also get at least one day each during their stint working in the museum so that they get a broad experience of the project. Wendy Reade (who also worked here last year) arrived last weekend to do about three weeks’ work at the museum conserving Zagora finds.

Also, from time to time, other specialists work at the museum. Last week, it was Jo Cutler, who was researching textile tools. I try to do a day a week at the museum so that I also get a broader experience of the project. Last week I went when Jo Cutler was there so I could produce a post on her work (which I published a few days ago).

Mostly the work requires intense concentration, and goes on in silence. But we all get together for a lovely lunch that Annette brings for us, and enjoy social chat and laughter then. (Annette buys the wherewithal for us to assemble bread rolls at the museum as she does for everyone at site – a big job.) The atmosphere is friendly and cooperative but mostly everybody just gets on with their job with a high degree of professionalism.

The finds washers work in the courtyard outside (it tends to be a bit messy with all the earth that has to be washed off the finds); Stavros, Beatrice, Wendy and the other specialists generally work inside the museum.

So, after all that, in answer to your question: Wendy does her artefact conservation work alone but she works in the same space as others. She is working during the last two weeks of excavation plus will work a week after the excavation.