by Irma Havlicek

with generous assistance from Beatrice McLoughlin and Stavros Paspalas

Zagora finds manager and coarseware expert

Beatrice McLoughlin is passionate about Zagora. So much so that when I first got to know her, I couldn’t imagine there was room for other passions in her life. However what I found was that she is a Zagoraphile, foodophile, oenophile, ceramicophile and general experienceophile. (Note: ‘-phile’ – denoting fondness for a specified thing; from Greek philos: ‘loving’.)

Beatrice’s mother was a ceramicist when Beatrice was growing up. She is now a weaver. (Note: ‘ceramic’ is from the Greek ‘keramikos’, from ‘keramos’, meaning ‘pottery’.)

Beatrice grew up with clay, kilns, pottery, old-fashioned kick-wheels, settling tanks, potting tools and firing experiments featuring large in her life.

Although she didn’t follow a career as a potter/ceramicist herself, the whole process fascinated her. She became familiar with different clays as powder and as paste; she wondered at their colours, textures and smells. And she watched her mother work, whether by hand or by wheel, and saw the clay animated and growing into shapes large, small, thick, thin, sturdy, fine, with and without spouts, handles, embellishments. Her eye was naturally drawn to the way things are made.

Beatrice keenly observed the process and saw which clays tended to be used for which objects; which shapes served which purposes. She can watch the process and imagine the resulting pot; or see a pot and imagine the process that produced it.

She would feel the finished object, inside and out, feeling for the marks made by her mother’s hands – which spoke to her of making, of process and of purpose.

Little did she know then that what she was learning simply out of curiosity and wonder would become the heart of the work she would end up devoting herself to as an adult.

Early studies

Beatrice grew up in Perth, and studied Ancient History at the University of Western Australia. There, she heard about a University of Sydney archaeological dig taking place at Torone in northern Greece, and volunteered to take part. As Beatrice described it to me in her inimitable fashion: “Torone is on the tip of the middle finger of the three fingers that look like udders off the top of the Aegean”.

This was the second dig Professor Alexander Cambitoglou, then Professor of Classical Archaeology at the University of Sydney, ran in Greece, from 1975 (after excavations ceased at Zagora in 1974).

Stavros Paspalas kindly contributed the following two paragraphs to provide a brief background about Torone.

Torone is a very important site which was occupied over approximately a 5000-year period, from c. 3000 BC until the Early Modern period. In classical antiquity it is best known, from the writings of the Athenian historian Thucydides, as one of the cities over which Sparta and Athens fought in the fifth century BC, though Herodotus also mentions the city in his account of the Persian wars earlier in the same century. Finds from the excavations have shown that the port settlement of Torone maintained contacts with overseas centres and that commerce must have been important to its economy in a number of periods. A most informative fourth-century BC letter written on a lead sheet refers to the timber trade, and it is known that the Chalkidic peninsula, on which Torone is situated, was an agricultural region; indeed, the wider region was particularly famous for its wine in classical antiquity. Exploitable mineral sources also appear to have been important in the area’s development in some eras.

Torone’s position on the sea lanes guaranteed that it was a significant centre, and impressive finds, many imported, have been recovered over a wide chronological span ranging from the Early Bronze Age through to the Ottoman era. In many areas of the site, strata from various periods have accumulated on top of one another, so the nature of the site differs considerably from that of Zagora. The latter is restricted to a few centuries of occupation (with the only attested activity located at the sanctuary area and fortification wall gate, continuing into the fifth century BC, approximately 250 years after the settlement’s inhabitants moved on), while Torone is a multi-period site where human occupation can be documented over millennia, particularly on the peninsula known to Thucydides as the ‘Lekythos’.

Beatrice’s first job at Torone in 1985 was in archives, and from 1986 she worked in the pot shed. She was the first person to wash the finds, to wash the mud off the fragments, to separate the ceramic fragments from rocks. (I learned at Zagora how difficult it can be to separate sherds from ‘tricky rock’ – this post about archaeological reconnaissance shows ‘tricky rock’.) She was handling a large quantity of pottery every morning – the first person to feel and see these pieces of pottery for thousands of years. Her sensitivity to the material and the meaning of the material quickly developed as she handled the sherds.

Beatrice learned early in her life to read pottery and know how it was made. To see or feel the joins and picture how hands worked those shapes. She gets joy from the information, the knowledge pottery gives her.

Beatrice also has an uncanny ability to solve pot jigsaw puzzles; to put pots back together even if sherds were found a distance apart on different dates. She will see the colour, feel the texture, and know that there was another sherd she has seen which will fit with one she has just picked up. I’ve seen her have a physical jolt of knowing she’s seen other pieces that belong to that piece – and she is mostly right about it.

Her sensitivity with pottery was quickly noticed by the Torone Finds Manager, Olwen Tudor Jones, who made Beatrice one of her second assistants. So, at the age of 22, Beatrice was helping to run the pot shed and process the finds, as well as working with the archives towards the end of the season.

Stavros Paspalas, one of the directors of the Zagora Archaeological Project now, had started working in the Torone pot shed with Olwen the year before, in 1984, and had also been one of Olwen’s assistants.

Recognising that Beatrice had a particular affinity with the larger coarse ceramic vessels at Torone, it was suggested that perhaps Beatrice would be interested in studying the pithoi, the ‘pitharia’ – very large storage jars from Zagora. Prof. Cambitoglou gave Beatrice permission to study the unpublished material, and Prof. Richard Green, the ceramicist of the Zagora expedition directed by Prof. Cambitoglou, supported the idea and became Beatrice’s principal supervisor for her Masters degree.

Her fate was sealed. She transferred to study Archaeology at the University of Sydney and has been immersed in the pottery of Zagora ever since. See our Artefacts page for more about pottery found at Zagora.

Olwen Tudor Jones – mentor

Olwen and Beatrice clicked, sharing a fondness for food and cooking, and this became a feature of their working life.

Beatrice gave me a lovely anecdote, speaking about Olwen, that conveys quite a lot about Beatrice and Olwen:

“I remember when she told me one day…. I was reading, trying to be a serious young insect. I was reading Dostoevsky or something. Olwen said, ‘Oh, yes. I used to read things like that. Back in the ’50s we used to wear caftans and drink raki while reading Dylan Thomas out loud. But now I prefer John LeCarre.’

“That was one of her throw-away comments, but she was that kind of person. She lived an amazing life. We have a scholarship now in her name, because she was always very supportive of young students, emotionally, financially – whatever would help. She was amazingly supportive in every single way.”

Olwen worked out the paper recording systems to register the ceramics: accurate descriptions, how to track objects and sherds, how to correlate information. Olwen taught Beatrice how to think systematically about everything to do with the excavation so that everyone, no matter what kind of researcher, had the ability to see the relationship between their material and everything else at a site.

Olwen’s main personal interest was the cooking pots and plain wares – because she always thought about the people who had lived at Torone as living people. What were they eating? How were they drinking? How were they socialising? It was all very alive to her; it came alive to her through the artefacts that had been excavated.

Beatrice and many others now working on Zagora feel immense gratitude for the help, guidance and support they received from Olwen.

Locally produced red coarse ware and imported pale fine ware

Coarse ware pottery tends to be larger, heavier and thicker than fine ware, and is made of coarse clay. You can see and feel the grains in it.

Fine ware pottery is wheel-made, tends to be smaller, lighter and finer than coarse ware, and is made of very fine clay. It is very smooth and slightly soapy or powdery to touch. This pottery is the ancient equivalent of the good china you get out for visitors. In the Early Iron Age, many of the fine ware shapes are associated with formal/communal drinking rituals: for example the kantharos, the oinochoe and the krater (see Glossary), the same shapes that become the standard set for symposia in the Classical period.

Fine ware pottery, in light crean or buff colours, was imported and used for serving food and drink. It is thought to have come from several different locations (e.g., Corinth, Athens and Euboia) as Zagora was well connected on trade routes. Zagora probably traded their agricultural produce with passing ships, in exchange for fine wares and other goods.

Fine ware was not produced at Zagora. However, the Zagora potters produced the coarse ware pottery required for cooking, processing, storing and transporting the food and drink that they consumed daily, or preserved for consuming in the winter months. It was produced from the local clay which was very identifiable, with visible flecks of quartz and schist in it, colloquially known as T (terra rossa). Because Zagora clays are iron rich but calcium poor, when fired in a kiln with lots of oxygen, they fire a rusty red – giving Zagora coarse ware its characteristic red colour.

It is to ZAP’s very good fortune to have Beatrice with her coarse ware expertise and Stavros (one of the three ZAP directors) with his fine ware expertise both as integral members of the project and working through the ceramic finds together.

Beatrice – Zagora coarse ware expert

Like many of the islands in the Aegean, it has a particular kind of layered and folded geology (layers of marble and schist) caused by the volcanic activity in the area which means it traps water underground, which resurfaces in the form of springs.

As Beatrice told me: “Because of the high mountain ranges that bisect the island, Andros can also have up to 50% more rain than than any other island in the Cyclades, and therefore more potentiality to grow crops of all kinds. The food traditions of Andros are rich in recipes for meat, vegetables and fruit, often in combination. My favourite is the traditional Andriote Christmas dish pork with quinces (Χοιρινό κυδωνάτο), flavoured with honey and cinnamon. The island also specialises in preserving both meat and fruit for the winter. Local specialities include pork sausages (loukaniko) and pork confit (that is pork fillets and sausages preserved in fat) for which festivals are held to assist in producing them; and a huge variety of fruits preserved in syrup (glyka or koutoulakia = spoon sweets). There is also a thriving dairy cattle industry here, which even produces butter (rare in southern Greece) as well as cheeses and yoghurts, alongside the more prolific sheep and goats milk products.

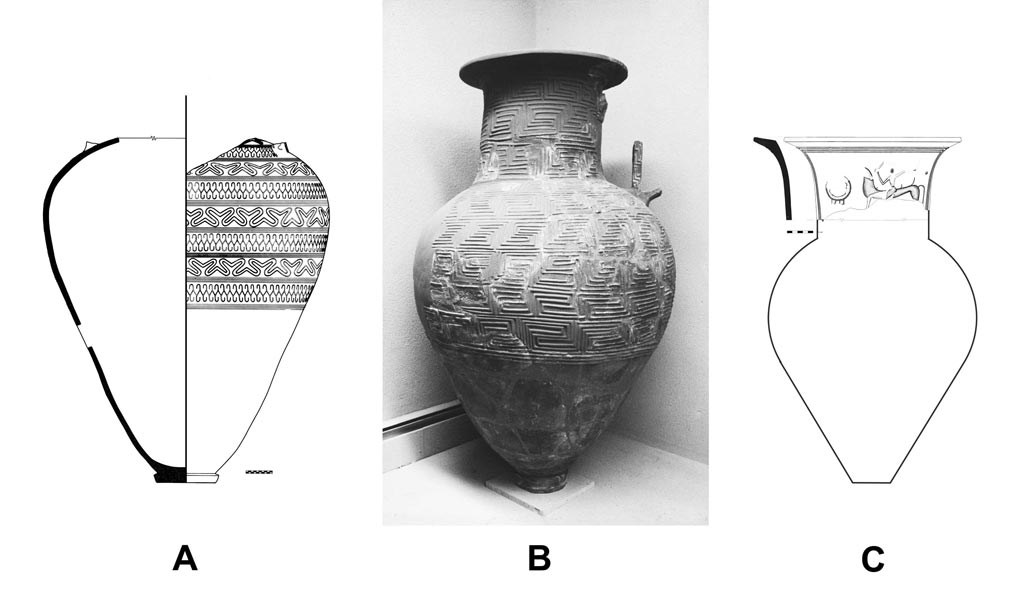

“Very large storage jars (pithoi, singular pithos [see Glossary]), of different types, are found all over the site, and there are benches in every house with pot nests in them where the storage jars were kept, which shows that every household made and kept several different kinds of foodstuffs in bulk. One of the large pithos types is highly decorated, sometimes with images from myths and other stories, and its bottle shape and the large size (up to 600 litres in capacity) suggest that they were used to store wine. A more simply decorated but equally large rounded pithos type is optimised for keeping its contents dry, cool and protected from pests: ideal for grain.

“Given the range and quantity of storage jars, and other pots for making preserves, and the wealth of imported pottery and other things, it is possible that the Zagorians may have also been producing preserved foods and wine to trade back in the eighth century. They have always grown and stored food, and it is likely that they have also always traded it, as is suggested by the amazing finds from the Neolithic site of Strophilas, on the promontory just to the north of Zagora, which is being excavated by Dr Christina Televantou.

“Regional food specialties are standard in the Mediterranean, and everyone has things that they say theirs is the best. They can grow everything here [on Andros] to have a good life, because they happen to have just the right kind of soil and rainfall and water catchment. They can even grow wheat, which is highly unusual on a Cycladic island, because most Cycladic islands just do not have enough rain.”

We’ve seen how Beatrice’s early familiarisation with the process of pottery-making has contributed to the research she is doing about Zagora. Her keen interest in gastronomy (note: ‘The practice or art of choosing, cooking and eating good food; the cooking of a particular area.’ From Greek ‘gastronomia’) has also contributed to her work – and is a key reason she was drawn to the coarse ware rather than the fine ware pottery.

The cooking pots are mostly small, between one litre and four litres in capacity, not dissimilar from the range of cooking pots we use most often in our kitchens today. This suggests that meals would have consisted of a range of different things to eat at each meal, reminiscent of the mezedes which is part of the Greek eating tradition today.

There are also much larger thick-walled cooking pots, which are better for slow cooking, perhaps for feasts or feeding helpers after the harvest.

Slow cooking has become popular again in recent years. Anyone who has eaten Greek-style slow-cooked lamb knows how tender it is, falling in juicy, flavourful garlicky, strips onto your fork.

As Beatrice told me, “The best vessel for slow cooking is a ceramic vessel because the clay takes in the heat and then retains it. Second best is iron for slow cooking.”

There is little archaeological record (and none at Early Iron Age Zagora) of metal vessels for cooking. This isn’t because it wasn’t used but because when metal objects became bent out of shape or a better design was developed or more important use was necessary (such as needing weapons if there was a military purpose), they were melted down and made into something else. With ceramics, once they were broken, they generally were just thrown onto the scrap heap or were sometimes used as fill with mortar in building, for example, house walls. Archaeologists are extremely grateful for this attribute of pottery – without which we would know much less about our human past.

She told me: “The Zagora settlement coarse ware potters made fantastic huge storage jars of different kinds, deliberately, functionally different.

“They made very gorgeous little cooking jugs, and some big thick-walled cooking vessels. But they also made really big thin-walled ones; I’m looking into what those are for. The same techniques were also used to make a magnificent thin-walled water jar, or hydria. I wonder if they developed the method for making very thin-walled large coarse ware pots at this site because they needed to carry large volumes of water. A very large thick-walled pot filled with water would have been too heavy to carry.

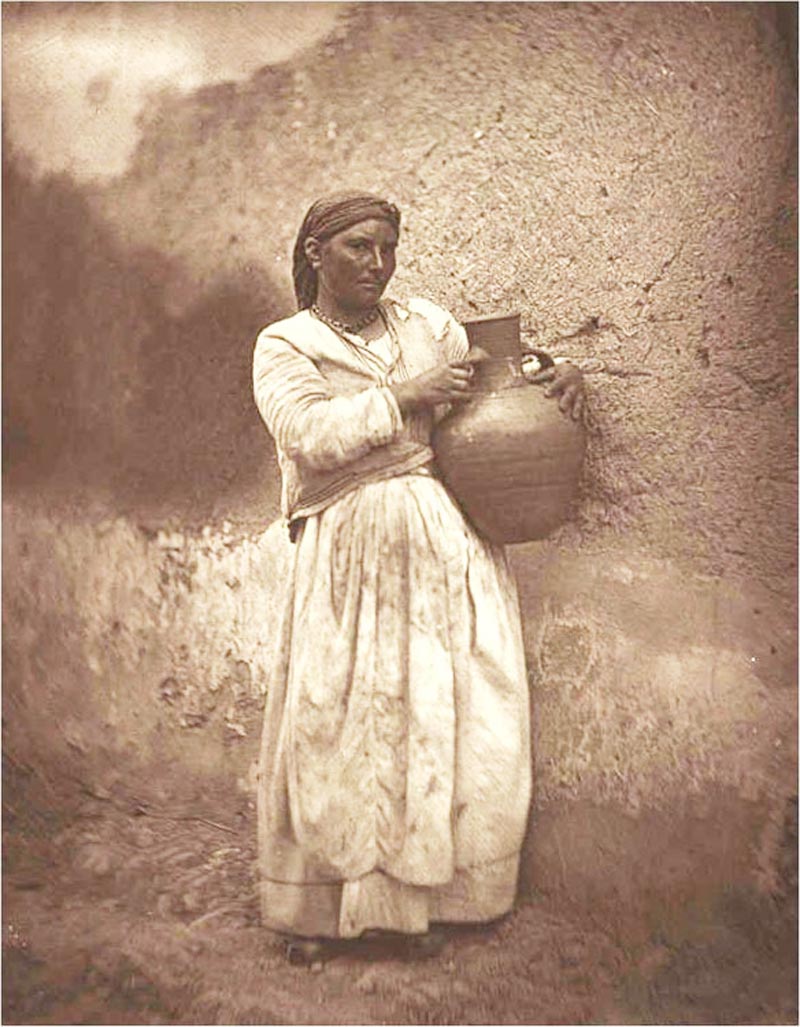

“In Greece before the introduction of piped water, water had to be brought from wells or springs. One of the major shapes of traditional Greek domestic pottery is the stamnos, for carrying that water. And they could have brought it back from the water source and then poured it into a jar. Stamnos production continued even after the introduction of plastic containers, because ceramic vessels are good for keeping water cool and sweet.”

Following is a photograph of a stamnos-maker’s children in the village of Aghios Demetrios on Cyprus taken in the early 1960s, showing how stamnoi are carried.

Beatrice’s research into Zagora coarse ware continues.