Craig Barker – Manager, Education and Public Programs, University of Sydney Museums

Why do you think archaeology is important?

I think archaeology is an extremely important area of study. Humans need to understand the past, and material culture (the physical evidence left by past societies) can provide incredibly valuable insight into how humans have developed, and lived in the past. I think we must learn from the past, and archaeology provides a tangible way of connecting with these people.

When did you know you wanted to be an archaeologist, and what was it that made you want to be one?

I have always been interested in archaeology ever since I was a young child. My mother blames the sandpit my parents bought me when I was a toddler! ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ came out when I was 8 but despite what many friends think, I had already decided I wanted to be an archaeologist before Indiana Jones. I may have flirted with the idea of palaeontology when I was six for a short while, but soon realised people were more interesting than dinosaurs!

I think I have just always had an interest in investigating the past.

I completed a three-year undergrad degree at the University of Sydney, doing a lot of archaeology courses (both Classical and Australian-related archaeology).

What study did you do to become an archaeologist?

I studied some language courses in addition, as well as some private archaeological illustration courses. I did my honours degree in Classical Archaeology, looking at the links between the origins of viticulture in Bronze Age Greece with the earliest appearance of the god Dionysos in written sources. I kept with the theme of wine when I worked on my PhD, which was focused on Hellenistic-period stamped handles bearing the names of annual magistrates and wine producers on transport amphorae made on the Greek island of Rhodes and transported to Cyprus. These names provide a chronological tool for the archaeological context they come from, as well as providing evidence for trade in the eastern Mediterranean in the aftermath of Alexander the Great. I was also lucky that while writing my PhD I spent a year based in Athens as the research Fellow for the Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens (AAIA) which was a great experience to access the libraries and research facilities of the various foreign schools based in Athens.

How long have you been an archaeologist?

I first started studying archaeology at University-level twenty years ago, and volunteered on Sydney projects from my first-year of studies. I got my first paid work as an archaeological contractor in 1995, which was also the year I completed my honours degree and participated in my first overseas excavation. I have been co-director of the University of Sydney’s excavations at Paphos in Cyprus since 2001, I completed my PhD in 2005 and I have been in my current employment at Sydney University Museums since 2006.

What are some of the key jobs you’ve had?

I have worked as a contract archaeologist on a variety of colonial projects in Sydney and in Tasmania. I have worked as a casual tutor and lecturer for the Department of Archaeology at the University of Sydney, and also did some casual work for both the Department of Archaeology and for the Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens – assisting in library work, and researching for senior scholars. Most of my work however has been in the museum education sector – I stopped counting after realising I had personally guided over 12,000 school students through the Nicholson Museum’s archaeological program several years ago! Outside of archaeology I have worked as a pub trivia host for a number of years – not particularly useful to archaeology, but it has helped my public speaking for lectures and presentations, and has given me things to do in a dighouse to keep the team amused some nights!

What skills or capabilities do you think are important to being a good archaeologist?

There are so many different types of archaeology (fieldwork, ceramic and other finds specialisation, theoretical, laboratory, data management, etc) that it is hard to think of a particular skill that is useful for all of us. A strong intellectual curiosity is something I know is common to everyone I have worked with, as is a keen sense of observation. Most archaeologists have a very good visual memory too. Archaeology works best when it is a collaborative discipline, so possession of openness to new ideas and theories as presented by the evidence is very useful. It also helps to be slightly crazy, I suspect.What advice would you give to someone interested in this career?

Read widely on a whole range of subjects to increase your influences on your thinking, and develop additional language skills as many useful studies are published in languages other than English. Visit lots of museums!

How do archaeologists spend their time?

I spend 5-6 weeks per year on my excavation in Cyprus (you can check out our Paphos, Cyprus blog – we’ll be there October/November, with our times overlapping with the Zagora dig), perhaps another 2 weeks at conferences somewhere in the world. My main work at Sydney University Museums takes up most of my time: guiding school students and other visitors through the Nicholson and Macleay Museums at the University, developing educational programs and public lectures and other public engagement programs. I would spend probably on average 1-2 hours a day working somehow on the Cyprus excavations – either in meetings with colleagues working on part of the project, researching in the library or online, working on related publications and our project website, or logistical planning for the next season (accommodation, flights, etc). Most of this work is done in the evening or weekends outside of my commitments to the museums. At the moment I am working on a small exhibition of Cypriot antiquities at the Nicholson Museum so my two worlds are overlapping a little at the moment!

What’s it like living in the ‘dig house’ during a dig?

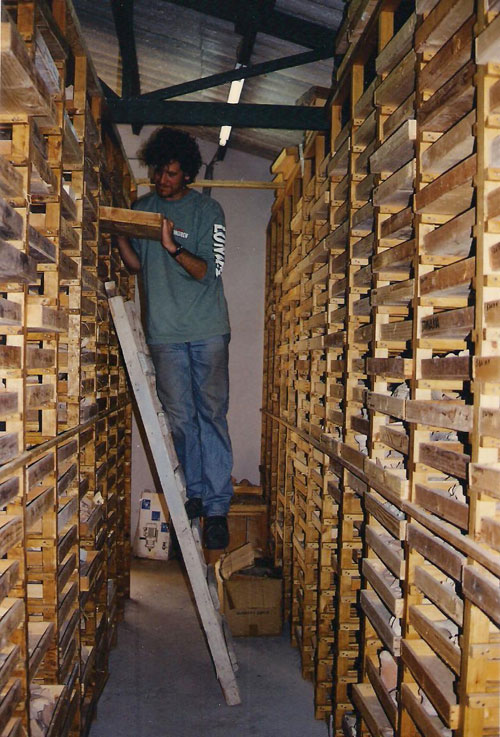

The project I am involved with in Cyprus had a dig house which was very large, so because we had a large team of workers, it involved taking a cook, drawing up work rosters for cleaning and other domestic duties. The dig house was close to the site, so the connection between excavation and finds processing and recording was close physically as well as conceptually. Traditionally the team works five and a half-days a week, but at any time of day or night there are people working with finds, photography and archaeological illustration, digbook and context sheets being written up and people discussing ideas and material.

This coming season will be the first time the team stays in hotel rooms and apartments while excavating, so while it will be more comfortable for the team the challenge will be to keep the team focused and united on the common goal, which is always easier when everyone is centralised in the one location.

Which parts of your job do you love, like, not so much….?

I’m not always so keen on early morning starts while on fieldwork! But seriously, I have always been attracted to the problem-solving aspects of archaeological research – what is the evidence telling us about life and the past. Also because I am heavily involved in education, I love talking to people and sharing my joy of archaeological and historical research and hope that others will become as passionate as I am about it.

How do you and your family cope with separation during archaeological digs?

I have been lucky in that my wife has been able to participate on the Cyprus project a couple of times, and a number of times we have met up overseas after the project so its not such a separation. But if a team functions properly with the right esprit de corp then you have a substitute family working alongside you during the fieldwork.

What’s been your worst experience in archaeology?

Nothing terrible, like all occupations you can have good days and bad days, but I have found the rewarding far outweigh the difficult days.

The only time I have ever tripped on trench strings marking the location of trenches in my life was in front of a busload of 40 Austrian archaeologists who were getting a site tour – ‘You shouldn’t have done that,’ one of them later told me!

What’s been your best experience in archaeology?

So many, but I have really enjoyed collaborating with a team of people with a common goal. There is still quite a buzz knowing you are the first person to hold something in millennia.

What’s your realistic and/or dream hope of archaeological achievement?

To contribute in some small way towards a greater understanding of the past. Contrary to popular belief, it’s not about grand discoveries but continually adding to the body of knowledge and interpretation.

What are some words you would use to describe your experiences as an archaeologist?

Overall fun. It can be hard work at times (both in the field and in the library). At times frustrating, but overall immensely rewarding. I’ve been able to travel to amazing places, to meet and work with amazing people and to play in the dirt. Is there anything better?