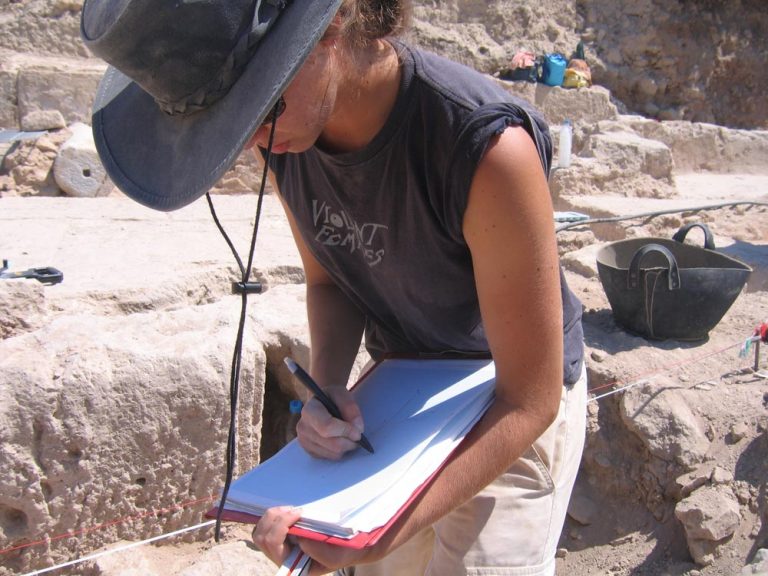

Kristen Mann – Archaeologist and PhD candidate

Why do you think archaeology is important?

It’s about understanding humanity. Knowing where we come from is so very important, although I also believe that the study of how people functioned in the past helps us to better understand how people function today. I think the humanities is one of the most essential areas of study for any society, and archaeology is integral to this. It really is the only access we have into the lives and cultures and actions of prehistoric peoples. Archaeology provides a very real and very physical connection with the past. Even in historic periods it grants further insights that history books can’t offer, particularly when dealing with the people that tend to fall through the gaps of historical accounts (such as women, slaves, children, working classes).

When did you know you wanted to be an archaeologist, and what was it that made you want to be one?

I didn’t realise I wanted to be an archaeologist until well into my gap year. I’m hardly the most decisive person, and at the time I was contemplating studying arts, graphic design or vet science. All I knew was that I wanted to travel, loved ancient history and art, and needed something active and outside. From a young age I also knew I didn’t care about earning loads of money, so long as I could do something I loved. Looking back it seems obvious really, but at the time archaeology didn’t seem real – it was the stuff of movies and legends to me really.

However, after high school I did the token Aussie rite-of-passage and went back-packing around Europe. This transformed my life. I no longer wanted to travel, I was addicted to it: the palpable need to see new places, meet new people and constantly have my eyes open to the wonder of it all was all-consuming.

Spending time in Greece and falling in love with the sites and museums there first made me consider archaeology as something viable. After chatting to a few archaeologists in Athens, I realised that it was a very real and very possible career, and that I could chase a life of travel, and follow a career that allowed me to work outside and to be forever learning and constantly stimulated. During and after my time in Greece, I started to look for ancient sites to visit everywhere I went. Everything I saw intrigued me, and cemented my decision to become an archaeologist. By the time I returned home, my mind was set, and nothing and no one could change it.

What study did you do to become an archaeologist?

I did a Bachelor of Arts for three years, with a double major in Classical Archaeology and Ancient History. I did every archaeology course I could – Classical and Near-Eastern – and every Ancient History class too. I also took courses in Classical Studies, Latin and Religion. I tried to take French, German and Spanish, but they sadly always clashed with every other subject on my timetable.

After my undergrad, I took a year off to volunteer and get fieldwork experience in Australia, Greece, Cyprus and Jordan. I thought of it as a trade apprenticeship really, ensuring I could do practical archaeology, loved it, and had some solid dirt experience under my belt before committing to further studies.

I then returned to do my honours year, writing a thesis on Early Iron Age (EIA) domestic space and social organisation in Greece. After taking another two years off (to work in contract archaeology full-time whilst also pursuing my second love and career in martial arts), I enrolled in my PhD and am currently studying the household material from Zagora – a topic which is very exciting at the moment! My research is part of a collaborative project, and I get to work with some of the world’s leading researchers in their field on the Zagora material. Plus, the EIA is very hot stuff right now in Aegean archaeology – there’s some great work being done in Greece by many amazing scholars.

I’m currently a third of the way through this, and am investigating how we can better understand the relationships and social organisation of ancient societies by studying the archaeological evidence for ancient households. I’m now living in Athens for a year as the Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens (AAIA)’s research fellow for 2012. This has been indescribably amazing for my studies. I’ve been able to participate in various projects and study seasons, including the exciting forthcoming Zagora excavations, study Modern Greek, and meet many amazing people and leading scholars from around the world. The academic community here in Athens is such a dynamic and vibrant hub, and the resources! The libraries and sites and material are just astounding. I love my job.

How long have you been an archaeologist?

I’ve been studying archaeology for nine years now, a practicing field archaeologist for 6, and am loving every minute of it!

What are some of the jobs you’ve had?

I guess it depends on how you define it.

I have had jobs that pay well, jobs where I learnt a lot and many that were just damn fun. All throughout undergrad I worked at least two jobs at the same time, at one point four, though only one (working as a guide at the Nicholson Museum) was related to my studies.

My first archaeological job was on a historical archaeology project in Parramatta. I remember it vividly, as I had been working and slowly killing my soul in a telemarketing job to save up for overseas. As soon as I found out I’d been accepted, I left my well-paid job to earn a pittance digging in hot hard clay and was happier than a pig in mud.

Since then I’ve worked on excavations and field surveys in Cyprus, Greece and Jordan, held a full-time position in an archaeological consulting firm, and sub-contracted on countless projects in Australia. My passion is for work in Greece and Jordan, but projects not directly related to my research always have new skills and perspectives to offer. A pivotal one was working on the Cumberland St site in the Rocks, as it really got me interested in household archaeology and site formation (my current research topic). And I’m really looking forward to my role as one of the trench supervisors at Zagora this year.

But I have to say that a small field survey I worked on in Jordan in 2007 remains the most life-changing. It was the end of a very intense year, full of many great things but also the deaths of several friends and family members. By the time I got to Jordan, I was exhausted mentally and emotionally. But the stunning landscape and the truly amazing people there quietly got under my skin, and helped me to heal and recover. Above all though, it was the project where I met and fell in love with my partner who is also an archaeologist. My life changed for the better with that project, in so many ways.

My whole life I’ve also had a second job as a martial arts instructor. All throughout my studies I taught Taekwondo up in my home town in the Blue Mountains, and eventually started my own martial arts school down in Glebe. My career in martial arts, while difficult to juggle with archaeology, has brought so much of value into my life. The belief in myself that it taught me, and the focus and discipline, has served only to augment my skills in archaeology, and I honestly don’t believe I could have achieved what I have today without it. The skills I gained in teaching and conflict resolution also transfer to archaeology surprisingly well.

What skills or capabilities do you think are important to being a good archaeologist?

I’d say passion and curiosity for sure. There’s a range of skills that are valuable, as there are so many niches in archaeology for people of different interests and skill sets to fall into. However you have to be passionate about what you do, and unfailingly curious, to really get the most out of this career: nothing else can carry you through the long hours of research or periods of financial difficulty.

The ability to express yourself clearly is vital however, as well as being attentive to detail. People who embrace challenges and are capable of working as part of a team really thrive in archaeology. A little bit of madness goes a long way as well – some of the best archaeologists I know are absolute characters.

What advice would you give to someone interested in this career?

Be inquisitive! Go see sites and museums. Don’t be afraid to ask questions of absolutely everybody on absolutely everything, you’d be surprised how many people are happy to offer advice or share experiences, or simply point you in the right direction. We all started with an email or phone call to someone asking if we could volunteer on their project. Getting that experience is the best place to start. Languages are also invaluable if you really want to pursue academic studies.

How do archaeologists spend their time?

As much as I love fieldwork, research archaeologists will only ever have a couple of months a year in the field, sometimes followed by a post-excavation study season of the material. The rest is researching, writing and giving lectures. You get a couple of glorious periods of being a ‘dig bum’ in your life – going from project to project for months on end. But they’re only in the hiatus years between studies, or while you’re still a student. After that, it’s all publishing and teaching and reading and writing. It’s different in contract work, but not by much. My time as a full-time consulting archaeologist was maybe 30% fieldwork, and the rest liaising with clients and community groups, writing reports, applying for contracts and planning fieldwork budgets.

What’s it like living in the ‘dig house’ during a dig?

Intense. That’s the best way to describe dig house living. I love it completely, but you throw a bunch of people to live together Big Brother-style, and you have an intensity of relationships and interactions all in one area: I’ve lived with up to 45 people in a very small space! I’ve forged some of my strongest friendships in the field – living with someone for six weeks like that is like having known them for six months. It’s not all sunny sunshine, tempers can fray towards the end, but again that’s just part of it all. There’s a unity that comes from living through the intensity of work hard/play hard and structured chaos that is a dig house.

Every dig has different rhythms, but usually we’re up early to make the most of the light, and work damn hard physically and mentally all day. Even at the end of the day, usually after a late lunch, you have artefact processing and, if you’re a supervisor, field notes to complete. The evenings tend to be great: free time (if you’ve got your work done) for throwing about ideas or just socialising and shenanigans one way or another depending on where you are. Some of the best projects will get each specialist to give presentations on their work in the evenings each week; I love those as I always learn something new. Although one of the reasons I love working in Greece is that there’s usually a beach nearby to throw yourself into after the sweat and the dirt of a long day on site.

Most projects are six-day weeks, with a day for exploring the area, and long projects will have a mid-season break with a long weekend to get to sites further away. Though really this break is just to preserve sanity! It’s communal living, so chores are usually distributed fairly, sometimes with a formal roster. Though many larger projects I’ve been on hire a local cook.

Which parts of your job do you love, like, not so much….?

I love the field. I’m happiest jumping fences and trekking through hellish undergrowth on surveys, or sweating it out in the dirt and physical exhaustion of excavation. I love puzzling out stratigraphy, and nothing can beat the awe of uncovering an ancient surface and realising that you’re the first person to stand in that room for thousands of years. I’m always curious about what I find, even if it’s not my area of study, and we all get quite proud and possessive of our trench and what’s going on inside it. I get totally absorbed in the puzzle of fieldwork, I tend to emerge blinking and surprised that the day has gone by so quickly.

I’m also a complete nerd and love the research side of things. I love learning, and chasing down obscure tangents of interest through chains of footnotes and references. I find it thrilling.

Probably my least favourite thing is writing grant applications or submitting abstracts for papers. I don’t know whether it’s the pressure involved in both actions, or just that it detracts from what I actually want to be working on. But that’s definitely my least favourite side of things.

How do you and your family cope with separation during archaeological digs?

To be honest, when you’re the one away and so completely absorbed in the life of fieldwork and dig house living, time flies and you can be so busy having fun that you don’t have time to miss people. I have a very big but very close family, and when I was younger it was hard being away, but now they’re used to my periodic absences. Skype is a life saver though.

I’m lucky that my partner is also an archaeologist, so we both understand how things work. One or the other of us is often away, sometimes we’re lucky to be away together. It’s always hard though when you’re used to having someone around every day to share things with, and then to be separated for long periods of time. But we know it’s the life we both chose.

What’s been your worst experience in archaeology?

I guess you have good days and bad days. I’ve been lucky to rarely have absolutely horrible experiences. My worst was probably making a fool of myself at a big international conference by mishearing the last comment and proceeding to ask a question on what I thought I had heard that was completely off topic. I was a student so everyone forgave me and was really kind, but it was a bit embarrassing. I’ve also been chased by a vicious dog out of a vineyard on a survey in Greece one time, but by the time I had scrambled over the top of the fence (with the back of my pants torn on the wire) I was giggling maniacally and thought it was hilarious.

What’s been your best experience in archaeology?

Oh there’s so many. I really love my job. But I’ll have to say it was working in Jordan. Not only did I meet my partner there, but the joys of working on a tell site (an artificial hill, formed through constant occupation since Neolithic times) cannot be described. The archaeology is fun, the puzzles absorbing, and working with local workmen an absolute joy and fabulous learning experience.

What’s your realistic and/or dream hope of archaeological achievement?

To actually make a contribution to our understanding of the past in some way. We’d all love to find something remarkable, and have dreams of uncovering something spectacular one day, but realistically I just want to contribute and participate in broadening our horizons one way or another.

What are some words you would use to describe your experiences as an archaeologist?

Complete and utter fun, invigorating, stimulating, dirty, dusty, dynamic, challenging and frustratingly hard sometimes (especially trying to start writing chapters or articles). I get to travel, see new things, discover more, and meet great people all the time – I love this job.