Paul Donnelly – Museum Curator and Archaeologist

Why do you think archaeology is important?

To the uninitiated it seems a cliché but it is apparent to anyone who is passionate about our past that through examining the lives and actions of those before us, we are far better able to understand the present.

Archaeology is a humanising discipline that emphasises the commonalities and connectedness of human beings in spite of seemingly disparate origins over vast stretches of geography.

We don’t have to go back too far to find common ancestors, and archaeology goes a long way to helping demonstrate this.

When did you know you wanted to be an archaeologist, and what was it that made you want to be one?

As a child I was interested in fossils and wanted to be a palaeontologist (or probably more accurately a paleontological astronaut!) I grew up in London and our holidays regularly included trips to Lyme Regis and Charmouth in Dorset which are famous for their Blue Lias limestone and shale fossil beds; most notably the spiral ammonites cast in iron pyrites or ‘fool’s gold’. The combination of great age and jewel-like appearance of these fossils was intoxicating to me and I still have vivid memories of my first discoveries – an ammonite at the age of ten, soon followed by a micraster sea-urchin, and my first chrinoid a few years later . . . I was a nerd before the term was coined and was in my element! By my early teems I was taking the tube train with a friend to the Natural History and Science Museums in London where, added to my paleontological interest I was exposed to the ancient buildings and Roman remains of central London. My father loved the British Museum so we would also visit there as well as St Albans (Roman Verulamium) that had been sacked by Queen Boudicca and I found my interests gravitating to the relatively more recent past and focussing on people and how they lived. In the St Albans Museum I was especially entranced by a dog-paw print in a Roman roof tile imprinted when a dog had idly trotted across it while the tile was drying – an otherwise unremarkable moment frozen from 1800 years ago. I was hooked and it is of great satisfaction to me that in my capacity as a curator I find myself responsible for a similar tile in the Powerhouse collection replete with similar dog print – maybe it was a job-lot?!

What study did you do to become an archaeologist?

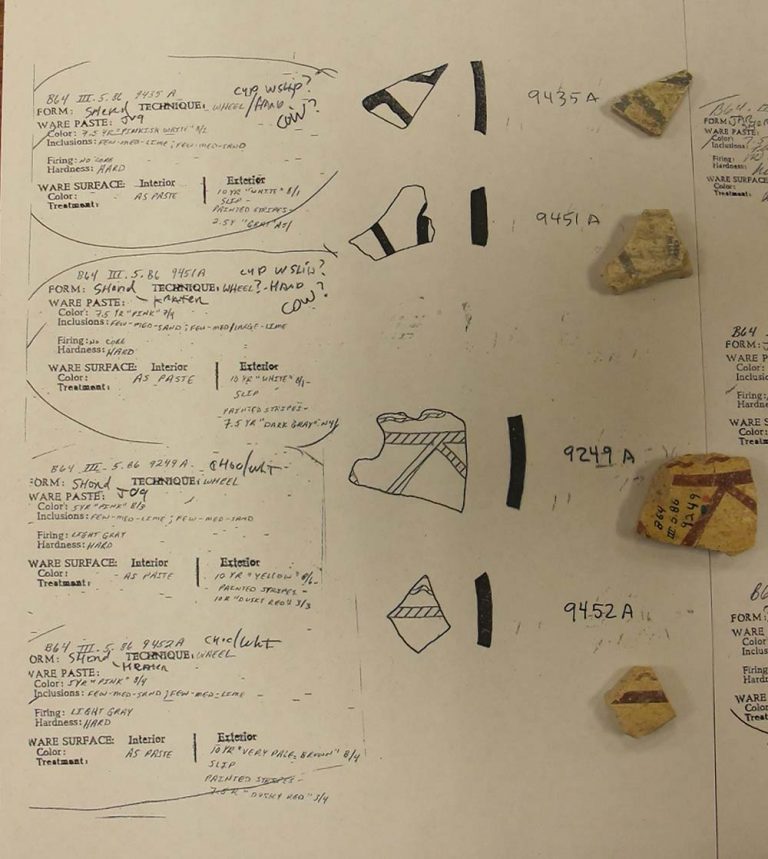

We arrived in Australia at a critical time just as I was turning eighteen and I had traditional vocational plans until the age to 22 when, while working in hospitality, I decided I would study archaeology and see where it took me rather than regret it. Thankfully my wife of the time was totally supportive and I did an honours Bachelor’s degree majoring in archaeology. After a museum-specific Master’s degree in Applied History at the University of Technology, I returned to archaeological studies to complete a doctorate. The PhD focussed on a Middle to Late Bronze Age ceramic produced around 1600-1400 BCE in the areas now spanning Jordan, Palestine, and Israel. Despite the appetising name of Chocolate-on-White, sadly no chocolate was involved, just a red-brown paint on a white slip background.

How long have you been an archaeologist?

I have worked at the Powerhouse Museum for over twenty years and feel it is more accurate to describe myself as a curator who is trained and still involved in archaeology. It is a great grounding for curatorial work and at the Powerhouse, even the curator of space technology is an archaeology graduate!

What skills or capabilities do you think are important to being a good archaeologist?

What has always driven me is a fascination about how our ancestors lived – a period beginning more recently in the 1950s and extending back millennia! I still get buzz when on an excavation I uncover a wall, floor, pottery, or even 3,300 year-old chick peas! I imagine when was the last time those things were seen, made, used or stored by a person in the distant past. In terms of practical skills I am a visual person and I am unsure whether this pointed me towards archaeology or if it was a happy coincidence that this ability became useful in my chosen discipline. I am also able to draw and this was my primary role for a few seasons.

What advice would you give to someone interested in this career?

You know in yourself if you have enough passion to stick with it and make it work. While a student I was frequently asked why I was studying something without a guaranteed job at the other end but I was determined to at least do the degree and see where it took me.

How do archaeologists spend their time?

My main job is at the Powerhouse Museum at which I am a curator in the design section responsible for parts of the collection that includes 20th century furniture, Australian pottery and glass, numismatics (coins and medals), and antiquities. I acquire through purchase or donation objects in these areas as well as research their significance, and answer public enquiries among myriad other enjoyable duties.

In terms of archaeology I am still involved in research that continues on from my PhD (and to that I can now add Zagora)! Over the last two years alone I have given conference papers written with two friends, Jaimie Lovell and James Fraser (in archaeology, colleagues frequently develop into friends) in London and San Francisco. While in the USA last year I also visited the Harvard Semitic Museum to see some pottery that continues from my PhD research.

What’s it like living in the ‘dig house’ during a dig?

Spending time while on excavation offers opportunities beyond archaeology such as visiting neighbouring sites, socialising with friends and learning from other team members both formally and informally. On spare evenings I have to confess I am partial to a game or two of Scrabble and while finding others who share this wordy desire is not always easy, when the Scrabble stars align it really is the icing on the cake for me! My previous experience has been in Arabic speaking countries so in my spare time on a dig I have always devoted some time to improving my vocabulary. In Zagora I will be immersed in a crash-course in Greek and one of the Greek-speaking team members, Archondia, has been assigned this duty!

Which parts of your job do you love, like, not so much….?

Aside from loving the archaeology, which is a given, I enjoy sharing the expeditionary experience with friends and colleagues. It is very special meeting up for a sustained time with friends at an archaeological site that you all get to know intimately and try to collectively understand over the rolling seasons.

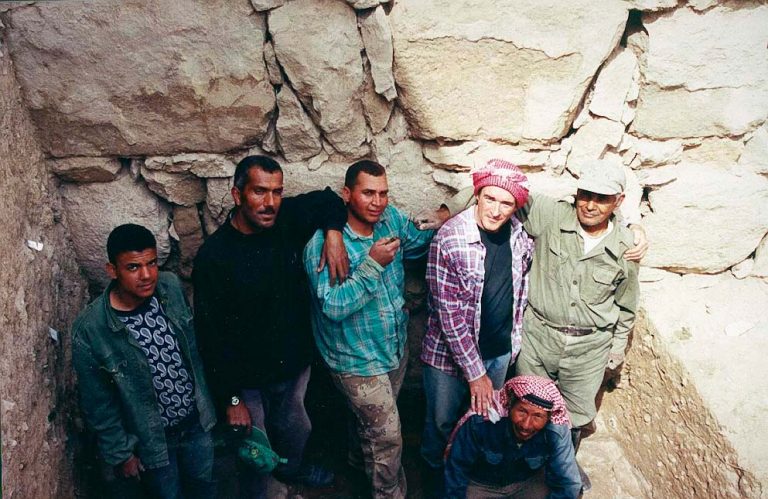

In my case Pella in Jordan where I have worked and researched since 1989 holds a very special place for me to the point it is very much a part of my sense of identity. The site is spectacular and we are in close proximity to other amazing places such as Jerash and Petra, as well as cites such as Damascus and Istanbul.

I don’t think there are many other disciplines that thrust people together for such intense and multi-faceted experiences.

What I don’t like is trying to work in the wind. Rain at least can reach a stage where the day would be called off as too difficult, but wind just has to be endured and flapping pages, flying labels and animated bags can drive you crazy! Zagora has a reputation as being very windy so that will be an experience I won’t relish!

How do you and your family cope with separation during archaeological digs?

My wife Tiffany is not an archaeologist but at Pella she found a number of roles in which she could use her skills and attend the dig which thankfully reduced prolonged periods apart. The arrival of children, however, changed this with Tiffany unable to attend a few seasons and to reduce the impact I attended half the usual length of season. I am glad that now the boys are older (7 and 4) they have been coming along for a portion of the dig at Pella in Jordan. Rather than stay in the dig compound we rent a house in the village with another dig family, Rachel, Ben and their children. As well as fulfilling the aim of reducing the period of separation, bringing along the family has added a whole new element to the experience. Seeing the boys play among the ruins, meeting the workmen and scrambling around other sites has added a whole new dimension to the experience. Zagora 2012, on the other hand, will be the longest I will have been parted from the family and we are hoping regular online contact through Skype will help. Unfortunately for me the season coincides with Tiffany and Piers’ birthdays, and our wedding anniversary which requires strategic planning of presents before I go!

What’s been your worst experience in archaeology?

In my younger years I was once caught in the extra sticky fly-paper necessary at sites near the Dead Sea.

In 1990 at Pella in Jordan my first trench, IIIP, was a nightmare of pits cut into pits. I was totally unprepared and in this sink or swim situation found myself grasping for the lifebuoy; it set me back years!

What’s been your best experience in archaeology?

It was such a thrill to be invited as a team member of Pella in the year I finished my Bachelor’s degree. My honours thesis involved the identification of Egyptian amulets in the Powerhouse Museum’s collection and was the period when what would be my two professional lives first intersected. An essential part of my thesis involved drawing each of the 25 amulets at twice life size from multiple angles. The then professor in charge of Pella, Basil Hennessy, invited me on the strength of those drawings. It is hard to believe it is 25 years ago.

What are some words you would use to describe your experiences as an archaeologist?

Fulfilling; satisfying; exciting; humbling

Is there anything else you would like to share with our readers?

A pleasure and privilege of archaeological research is that in tandem with getting to know the people of the past, the long-term and annual digging seasons allow the team to get to know the locals.

At Pella I have seen children grow up and have their own children, mothers and fathers become grandparents, and share in mourning the loss of the old. I sometimes suspect I value this aspect as much as the archaeology.