About Zagora

The settlement of Zagora

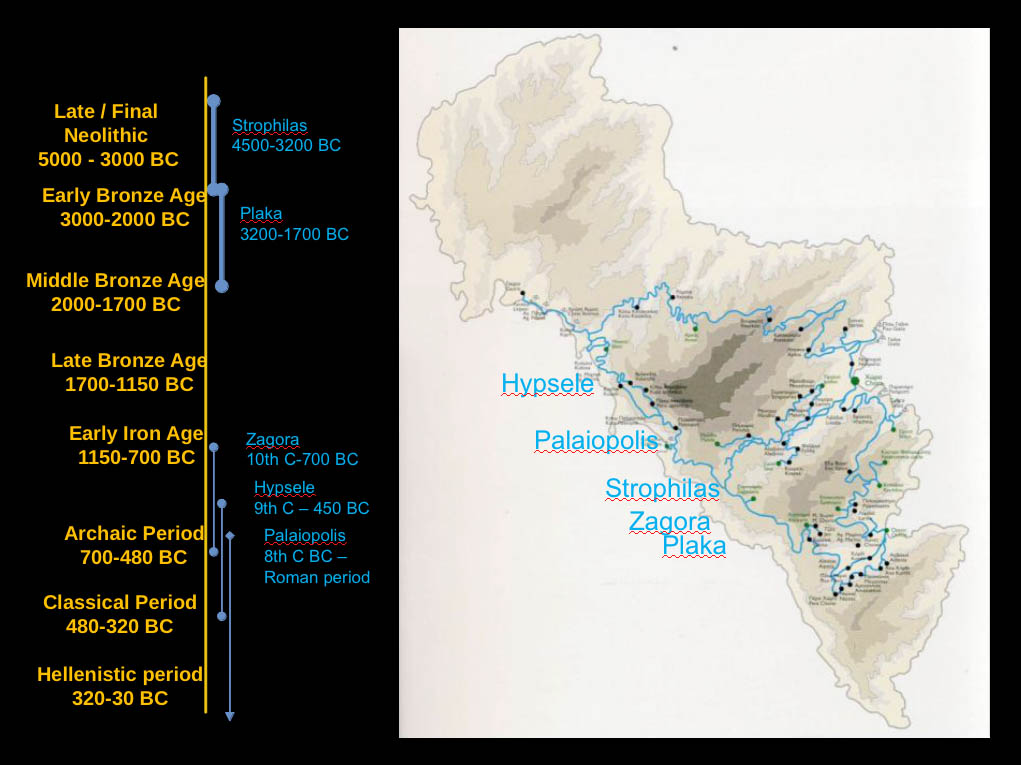

The site of Zagora is situated on a peninsula on the south-west coast of the island of Andros in the Cyclades. Zagora is almost unique among central Aegean Early Iron Age sites in that the complete settlement, covering an area of about 6.7 hectares, has been preserved undisturbed by later occupation. It is renowned for the extensive 9th-8th centuries BC settlement, with some indications that it may have been occupied in the late tenth.

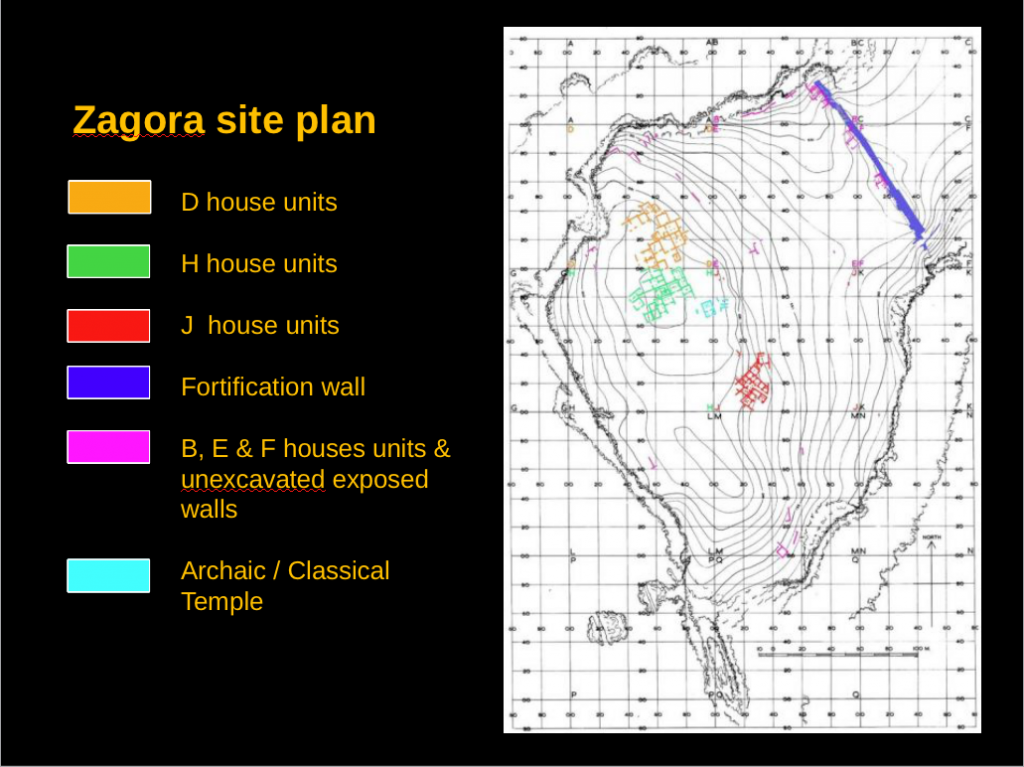

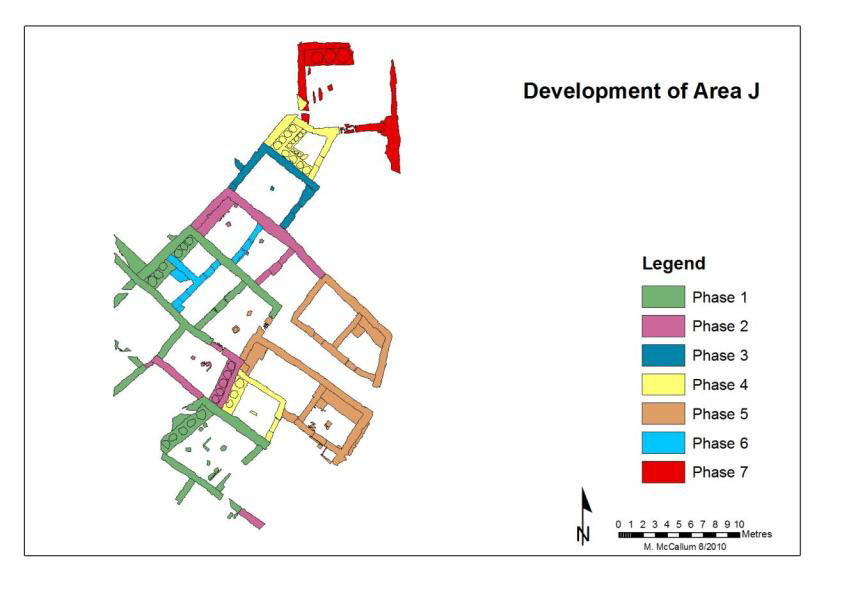

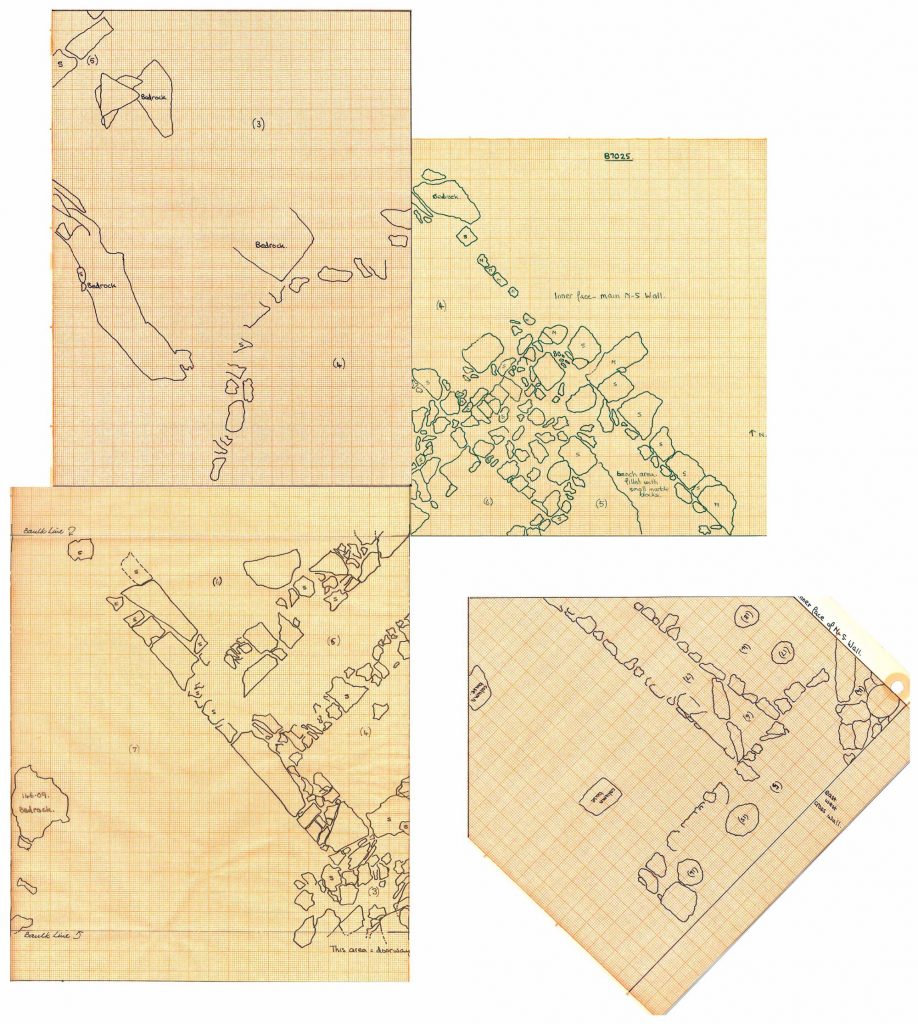

Australian excavations carried out between 1967 and 1974 uncovered 10% of the total settlement area, including 55 definable stone built rooms which together represent at least 25 houses organised in neighbourhood clusters much like Greek island villages are organised today. The video below (2 mins 43 secs) provides a glimpse of the Australian archaeological project at Zagora in the 1960s/70s.

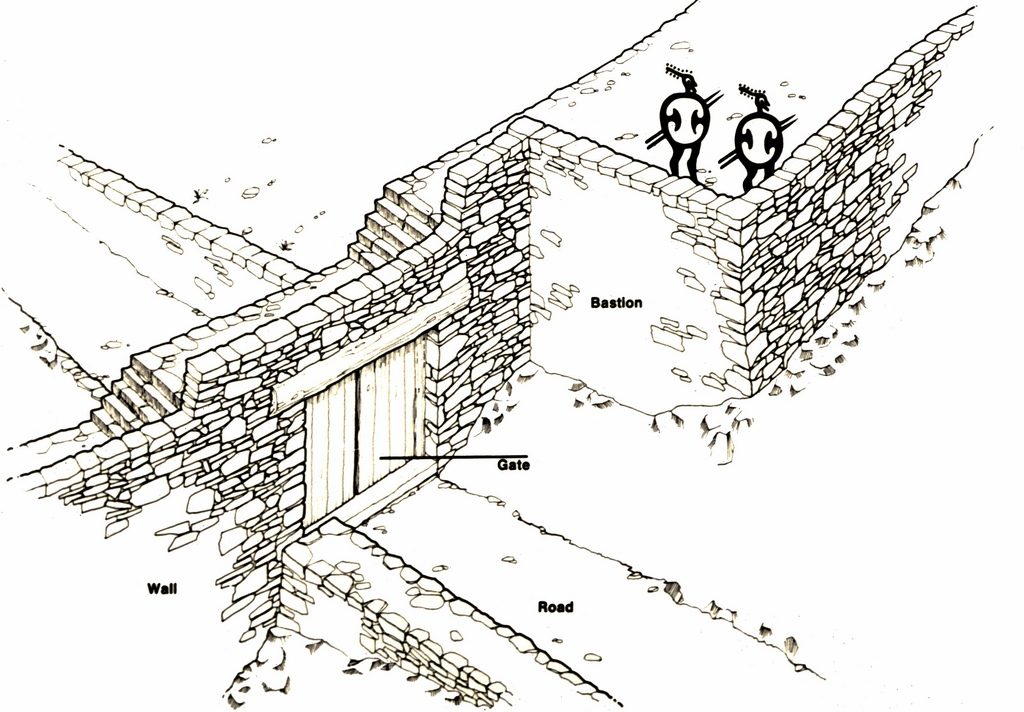

An impressive fortification wall with a well-protected gate were revealed, as well as a sacred area, which continued to be visited after the settlement was abandoned at the end of the 8th century.

The Australian excavations of the 1960s and 1970s was led by Professor Alexander Cambitoglou (The University of Sydney) under the aegis of the Archaeological Society at Athens.

From 17 October to 27 November 2012 we reopened the excavations using 21st century methods of geophysical survey, and digital recording mapping to add breadth and depth to our knowledge of this unique town. The excavation continued for a similar period in late 2013, and will continue for a similar period commencing in September 2014.

Geographic location

The island of Andros is perfectly situated on the sea lanes connecting central Aegean trading cities, particularly those of Euboea, such as Eretria and the mainland coast opposite that large island with areas in the central and eastern Aegean, and even further east, as well as to the northern Aegean and via the Dardanelles into the Black Sea.

There is plenty of evidence that the inhabitants at Zagora engaged in local trade networks as over 90% of the decorated pottery is imported; originating from its fineware pottery producing neighbours, including Euboian towns such as Eretria and Lefkandi, and islands such as Naxos and Paros, as well as Athens and Corinth further afield.

The fortification wall

The fortification wall is a very significant example of military architecture of the Geometric period. It protected Zagora on its vulnerable landward side, and once the settlement’s inhabitants relocated, it fell into a state of disrepair.

Some restoration work was undertaken on the gateway during the 6th century BCE during the time when the temple was built. The wall was built out of a mixture of marble and schist and featured an elaborate gate used for the passage of entrants to the site.

Domestic architecture

The layout of the houses excavated at the Zagora site suggests that the inhabitants preferred to build their houses in blocks rather than detached buildings. Some of the characteristic features of houses included a central rectangular hearth in the floor, stone benches along the walls used for the storage of large pithoi and bins which were located in both rooms and courtyards for the storage of essentials such as grain and water. Many houses featured courtyards which separated the front of the house from the streets.

The roofs of houses were flat which would have assisted the capture and storage of water since springs or wells have not been identified at the site. The roofs also featured a kerb of heavy stones to prevent the roofs from being blown away by the northerly winds affecting the island all year round.

The sanctuary and the temple

Two major phases of development of the sanctuary have been deduced from the stratigraphy and pottery findings at the site. The excavation of animal bones at the temple suggests that piglets and young lambs were used as sacrificial offerings.

The Geometric sanctuary area is believed to have featured an open-air sacred area around an altar. The temple is believed to have been constructed later during the 6th century BCE due to the presence of two drinking cups from the 6th century BCE. The temple was built predominantly of schist and featured a square shaped main room containing the altar and the image of the worshipped deity as well as a closed anteroom.

The cemetery

Evidence of three burials in one particular area beyond the fortification wall indicates the location of a probable cemetery of the Geometric town. This area has not been explored as it is a very fertile area and has therefore been cultivated continuously over the centuries and is unlikely to reveal well preserved artefacts.

The early Iron Age

The Early Iron Age (1100-700 BC) represents the period between the collapse of the Bronze Age civilisations of Crete, mainland and insular Greece and the establishment of societies based on city states (‘poleis’, sing. polis). This period as we can gauge from the earliest (and relatively limited) Greek historical sources was a complex one. Its earliest phases in particular have traditionally been thought of as a Dark Age, but new evidence shows that the contacts and achievements of Aegean islanders and the inhabitants of other areas of the Greek world were many. The sources are almost exclusively archaeological and, although they show major changes in society and settlement organisation, they also reveal elements of continuity and regional diversity in response to the Mycenaean and Minoan collapse. The eighth century saw the most profound changes, including the emergence of more elaborate settlements, more impressive sanctuaries with richer dedications, new contacts with the eastern and central Mediterranean, and the re-appearance of writing. 1

Major questions about the Early Iron Age

Early Iron Age population movements: where, why and how?

- What was the nature of early sanctuaries, why did they develop the way they did, where they did, and why? What was their role to the communities they served?

- Why and how did the social organisation of settlements change and how can we read that from the architecture and objects left behind

- And what does all of this have to do with the birth of the ‘polis’ – the first step in the development of the early modern state?

All the questions above are interrelated, and none can be answered in isolation. While Zagora cannot supply evidence to address all of the questions above, it is ideally suited to addressing questions concerning changes in social organisation of whole communities rather than, for example, the elite who could afford burials, and are now relatively easily recognised in the archaeological record.

It allows us to understand how people lived their day to day lives, what objects were used in the home or courtyard for processing farmed produce, and whether some objects were used only by the occupants of some houses but not others.

This provides a greater appreciation of the significance of objects that turn up at sanctuaries and in burials that are not found in settlements and – arguably more importantly – the significance of objects that are used in every day life, and the very functions that make them special enough to be given to the gods or buried with you when you die.

The environment 2

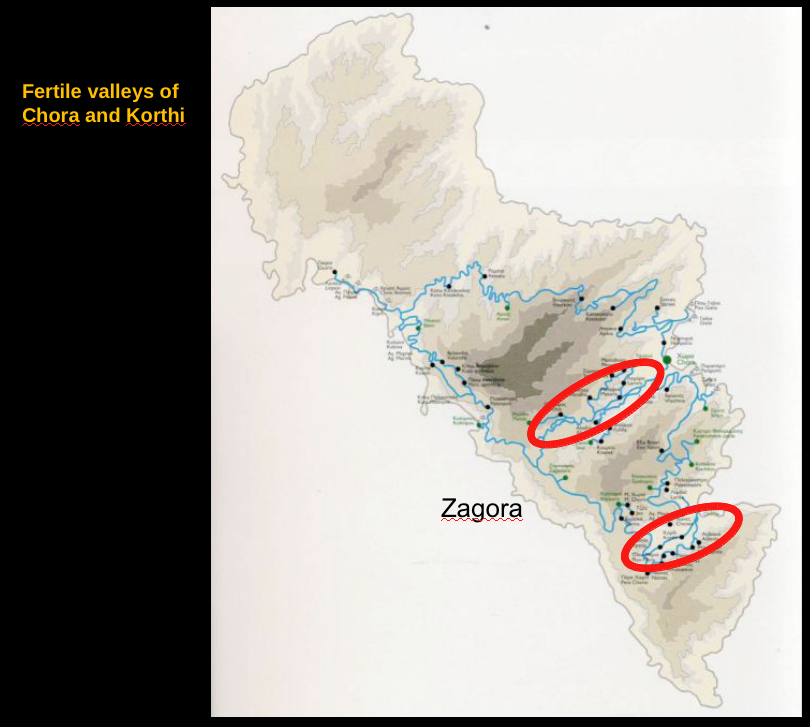

Andros has a very long history of agricultural wealth thanks to its high annual rainfall (50% higher than other islands in the vicinity) coupled with a schist based geology allowing for a high level of subterranean water catchment 3, which provide the water for the many natural springs all over the island. Indeed Andros has so much water that it even produces its own bottled sparkling mineral water.

There are indications that the settlement of Strophilas (just to the north of Zagora) was already trading in agricultural surpluses by the Final Neolithic period 4.

In the 1880s CE, Andros was described by the English traveller Theodore Bent as the best wooded of the Cyclades, second only to Naxos in size and beauty, and the Chora valley as ‘one of the most fertile valleys in the world’. The abundance of water has been noted since antiquity, sharing with the islands of Hydra and Kea the epithet ‘hydroussa’ (i.e. ‘watery’).

Until the end of the 19th century when mercantile shipping became a focus for the economic prosperity of the island, specialty agriculture was the main source of surplus income – silk and lemons to name but two products. Current artisanal specialities produced on the island include cow’s milk cheeses and preserved fruit products, and Andros has always had a reputation for excellent vegetables and meats, reflected in the local specialities involving beef, pork (particularly preserved pork) and lamb in combination with leafy green vegetables or fruit like quince.

What we know so far

The settlement thrived and grew throughout the ninth and eighth centuries until, for as yet unknown reasons (possibly environmental, as earthquake damage has been recorded at Hyspele [a site to the north of Zagora] at this time), the inhabitants left. Another theory is that the water supply declined – possibly connected to the earthquake activity if this caused changes to the underground water supply – and became insufficient to support the settlement.

Because the rooms of the preserved houses were all built substantially of stone, one wall abutting the next as the neighbourhoods grew – we have an exceptionally good idea of how the addition of each new room or house would affect those already there, which suggests the closeness of the relationships between the people living in them.

Lots of pottery and other objects were left behind stacked up neatly in a number of the rooms. These caches of objects provide us with our best snapshot of the daily life of the Zagorians.

They include many kraters, jugs and cups (the kinds of items later usually associated with the classical symposium) which indicate use in social gatherings – philosophical, religious or just convivial sharing of wine. The wide distribution of the kraters across all the house types at the site is very interesting as it has often been proposed that symposiastic rituals are the preserve of the elite.

Also found have been household implements such as pounders and a pestle and grinder, cooking jugs and tripod cauldrons with smoke smudges on their bellies showing the nature of their use, storage jars (huge, medium and small) to provide the raw material for meals, feasts or drinking parties. There were also a large number of spindlewhorls and loomweights, providing evidence of spinning and weaving practices, and echoing the image of Penelope, Odysseus’s wife, weaving (and – in her particular case – unravelling at night) while she awaits his return.

Animal bones were also recovered belonging to sheep, goat, cattle pig, equid and hares providing evidence of the diet of the inhabitants as well as husbandry practices. The spinning and weaving materials also suggest that sheep were kept for their wool. The recovery of hare bones suggests that hunting practices occurred.

What we don’t know: where they went and why

Given the continued use of the sacred area into the 5th century some of the population may have simply moved into existing neighbouring settlements on the west coast such as Hypsele, which continued to be inhabited until the end of the 6th century BC, or Paliopolis, which would become the eponymous Classical city of the Andros [aka Ancient Andros], but some are likely to have joined the ships heading west with adventurous Euboians and Naxians among others to establish farming communities in Sicily and Southern Italy, and some of them perhaps a little later went north to help set up the three Andriote colonies in the Chalkidike peninsula and a fourth, Argilos, slightly further to the east.

1 http://www.arch.ox.ac.uk/classical-archaeology-periods.html; http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/angk/hd_angk.htm

2 http://androsfilm.blogspot.com.au/

(If you open it in Chrome and use the translation option, it is quite navigable for the non Greek speaker.)

3 Brun, P., Les Archipels égéens dans l’antiquité (Ve-IIe siècles av. notre ère), Besançon, 1996, 34-35.

4 Televantou, C., “Strofilas: A Neolithic Settlement on Andros” in Brodie, N., Doole, J., Gavalas, G. and Renfrew, C. eds., Horizon. A Colloquium on the Prehistory of the Cyclades, Cambridge, 2008, 43-54.