The specialist work of Dr Melanie Fillios, Zooarchaeologist

Web content producer

Dr Melanie Fillios is an archaeologist who specialises in researching faunal remains (animal bones) found during archaeological excavations.

She is not a palaeontologist whose job it is to study animal bones in order to develop an understanding about the development and history of that species of animal. Melanie is a zooarchaeologist whose job is to study the animal remains in order to better understand how those animals impacted upon the lives of the humans among whom they lived – and died.

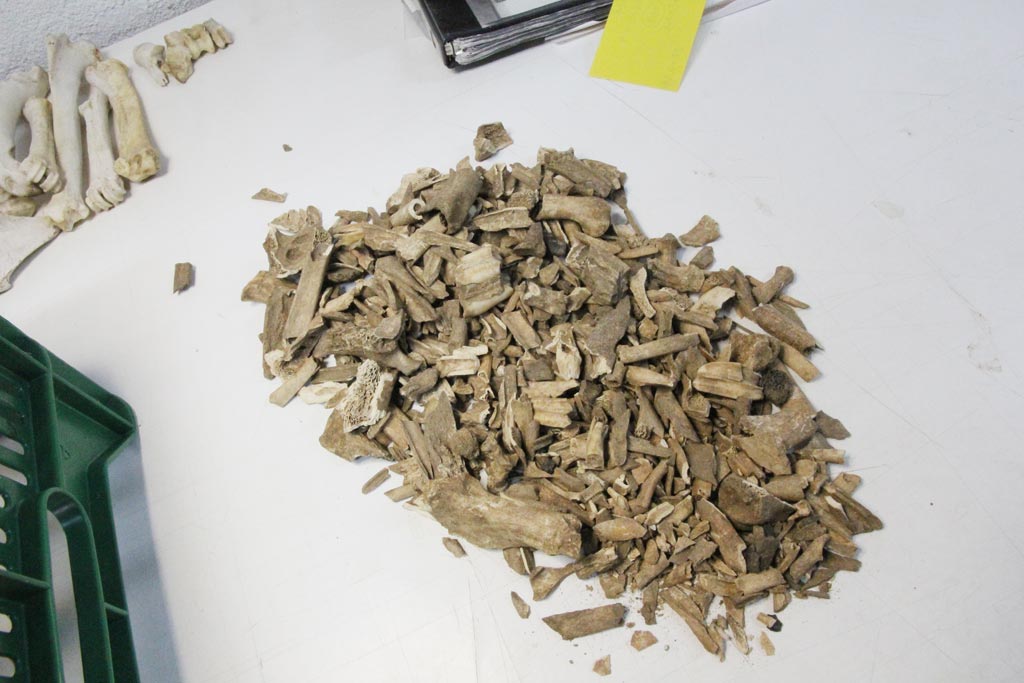

Melanie is spending three weeks working at the Andros Archaeological Museum, examining and cataloguing the bones and bone fragments which have been unearthed at Zagora during the excavations of 2012-14. She arrived during the last days of excavation and is remaining after excavations with members of the study season group at Chora (the capital of Andros, where the museum is located).

The bigger the sample size, the more evidence Melanie will be able to glean from the bones. One bone is not very telling. As Melanie told me, one bone tells us: “So they had a sheep…. A laundry list doesn’t tell you anything.”

She estimates that she will have examined up to 10,000 bones or bone fragments during the three weeks of her work here. Hopefully this large sample size will enable us to realise a much clearer picture of the lifestyle at Zagora nearly 3000 years ago.

I spent some time with Melanie at the museum where she kindly explained and demonstrated her working process, as well as telling me how she came to specialise in the area of faunal remains.

Melanie’s background

Melanie began her university studies at Vanderbilt (Nashville, Tennessee), concentrating on Anthropology when, in the second year of her undergraduate degree, at the age of 19, Professor of Anthropology and Archaeology, Mark Plew, suggested that Melanie may find it interesting to focus more on archaeology. Melanie accepted his invitation to spend eight weeks on an archaeological excavation in Idaho working on a Paleoindian site to see if archaeological excavation and research suited her.

The eight weeks of work took place in the desert, with extremes of heat, no toilets, no water apart from what was carried in…. And it hooked her. (Some of us might say: fair preparation for Zagora.)

After her undergraduate degree was completed, she did some consultant/contract archaeology and then returned to University to do an MA. She chose the University of Minnesota which had the combination of Anthropology, Archaeology and Classics that Melanie wanted to pursue.

During her MA studies, Melanie was invited to participate in a Neolithic dig at Halai, 90 minutes north of Athens. Her knowledge of Greek and Latin languages helped her in this work.

In the US, it is general practice for a PhD to do two years of course work, during which you determine your area of specialisation and your thesis topic, and then you spend three years researching and writing your thesis.

During the course work phase of her PhD, Melanie was invited to be a trench supervisor at Helike, an Early Bronze Age site in the Peloponnese in Greece. There were many Roman finds here but the project director was more interested in the Early Bronze Age material, among which were many bones which had not yet been studied.

Because Melanie had studied Osteology (the study of human bones) and also taken courses in Faunal Analysis (animal bones), she was asked, and agreed, to undertake a study of the bone material. This work deepened her interest in what could be learned about a society through the study of the animal bone remains on a site. And she decided the study of faunal remains would be the focus of her PhD thesis.

After her PhD, Melanie worked as a research assistant for Dr Judith Field at the University of Sydney. During this time she worked with Judith on a project at Cuddie Springs (near Brewarrina, in central north New South Wales [NSW]), where Melanie excavated and analysed bones of Australian megafauna of the Pleistocene.

After this, Melanie got an Australian Research Council (ARC) grant for a four-year experimental zooarchaeology study in outback NSW.

Since then, she has stayed in Sydney working on a variety of contract archaeology projects and with some teaching work at the University of Sydney – including being examiner of the Honours thesis of Rudy Alagich, our team member who has worked since 2012 on the Zagora project. Rudy is now furthering his animal bone studies at Oxford University. I find it interesting that Melanie and Rudy, our animal remains specialists, are both vegetarian.

What can faunal remains tell us about the animals?

– species of animal

– breed of animal

– sex of animal

– size of animal

– age of animal (factors which can help determine age include teeth, the size of the animal, and epiphyseal fusion. In some species, including humans, some bones are separate at birth but fuse together as the animal grows; this means the degree of fusion is an indication of the state of maturity or age of the animal)

– the part of the body it is from

– whether the animal is wild or domesticated

– the distribution of different animal remains across the site

Some bones are more diagnostic than others (for example, Melanie can identify from horns whether they come from cattle or goats or sheep).

What can faunal remains tell us about Zagora?

Information about animal remains can tell us a great deal about Zagora society – and much more than just what the settlers were eating.

Assessing which bones from which animals (sex, age, species, breed) occur in what proportions in which locations across the site can provide evidence about their herd management techniques, possible trading patterns, and use of the animals.

The diet of Zagorans

The distribution and proportion of wild and domesticated animals can provide information about the Zagorans’ diet, which can provide further evidence about their likely health.

The age at which animals appear to have been butchered along with the season when they were butchered can provide an indication about whether the animal was primarily used for wool or milk or meat production. Melanie will look for such evidence across the species and breeds of animal remains found at Zagora.

If a larger number of a species/breed/age of animal is butchered at a particular season, this might indicate what that animal was used for – for example whether a sheep was more likely used for wool or milk or meat.

The proportion of male to female animals at different ages can also provide evidence of the way the animals were used. For example, more adult female sheep or cows suggests they were used for milk, males of the species having been slaughtered when they were younger for meat.

Husbandry practices

Melanie can get an idea from some faunal remains whether an animal was wild or domestic. For example, wild and domestic animals have different diets which cause different wear on teeth.

Other anatomical changes can also be indicative of animal domestication. For example, domesticated pigs have shorter snouts than wild pigs which need longer snouts for searching out food. It can be surprising how few generations it takes for anatomical changes in species in response to their changing environment. If a pig is regularly fed by humans, it no longer requires some of the physical and other characteristics of a pig fending for itself in the wild.

The distribution and proportion of wild and domesticated animals can tell us what animals the settlers were hunting or fishing for, what animals they were farming, and about their herd management techniques.

Draught animals

Marble is the rock found naturally at Zagora. All of the schist at Zagora was brought down from surrounding areas. It’s possible that draught animals were used to carry schist and other requirements (possibly water – but how they sourced water for the settlement is one of the big questions we are trying to find answers for) to the settlement from surrounding areas.

Secondary economic purposes

If many broken bones are found, that may indicate use of the animals for secondary economic purposes, for example, production of gelatine or making glue.

Other possible secondary economic purposes could be extracting tallow (fat) to make candles, or tanning to process animal hides.

We don’t have any evidence of candle-making or of tanning at Zagora. But these economic production activities could be indicated by certain features of animal remains such as a high degree of bone fragmentation.

Animal hides could have been used to make ship sails, clothing (for example footwear or coats), or as furnishing. The doorways of previously excavated and published buildings at Zagora generally have lintels (the horizontal slab above the doorway) and jambs (the vertical slabs at each side of the doorway). Evidence of doors has not been found, suggesting they may have been made from an organic material that has decomposed – such as wood or animal hides.

Discarded animal bones may also have been used in construction, along with rubble or ceramic sherds, to fill holes, to help create flat floors or in the creation of solidly packed hard road surfaces.

What animals were there at Zagora?

However we know that bones from the following animals were found during previous excavations: ovicaprids (this category includes both sheep and goats whose bones can be difficult to distinguish from each other), pigs and cattle.

Isotope analysis

After Melanie’s assessment of the bones, some may be sent off for isotope analysis, which can reveal what grasses the animal was eating and the proportion of meat to other diet in the animal, as well as the season in which the animal died. If relatively high numbers of particular breeds of animals were slaughtered in a particular season, that could tell us something of their animal husbandry practices.

Change through time

Melanie hopes to be able to see changes through time over the 200 years of the Zagora settlement by seeing changes in the types of animal bones she finds in the different depositional layers that have been excavated. These changes may indicate lifestyle changes over the period of the settlement.

Process of Melanie’s work

Bones arrive in clear plastic bags, labelled to identify from which part of which trench they were excavated, on which date, and any other relevant information. ZAP team members working as finds assistants wash them clean of earth. Clean bones from each unit are then laid out in a tray and photographed by a finds assistant.

The finds are then rebagged and given to Melanie, who spreads the bones and bone fragments out across a table in order to sort them into species and what kind of bone (eg, tooth, femur, etc.) If there is anything diagnostic, for example a tooth indicating age, a horn indicating species and/or breed, a joint indicating body part, Melanie will take a further photograph of that bone. Or if there is something of interest, for example, a cut mark which was likely made by the butcher, Melanie will photograph and take a closer look at that also. These kinds of bones can help to build up a picture of how the animal was used, slaughtered, disposed of, etc.

Melanie’s extensive experience in her field mean she can instantly identify and sort most of the bones according to species and body part. She can see if there is a cut mark (made by a butcher with a sharp cutting implement) or if plant root growth underground has marked the bone in a way that has marked or obscures the natural surface of the bone.

If there is something notable about any of the bones, for example a cut mark or indication of pathology (disease or trauma), Melanie will take one or more additional photographs of it.

Data integration

The text and photographic data will be fed into the University of Sydney Heurist database, so that the faunal remains information will be incorporated with all the other Zagora data – architecture, finds (ceramics, slag, obsidian, seeds, etc.) – to build as complete a picture as possible about the way life was lived at Zagora almost 3000 years ago.

All this data will then be available to be very quickly cross-referenced in whatever way is required by Zagora researchers.