by Irma Havlicek

with generous assistance from Beatrice McLoughlin

AAIA Research Officer, archivist and archaeological database proselytiser

(This is part 2 of a profile of Beatrice McLoughlin. Part 1 focuses on Beatrice’s expertise with coarseware.)

Beatrice is the Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens (AAIA) Research Officer, looking after the archives relating to the AAIA’s archaeological excavations: Zagora and Torone in Greece.

She has been researching the Zagora legacy data – that is, the information out of the initial Australian excavations at Zagora in the 1960s and 70s for some 20 years.

Beatrice is in charge of the ‘Zagora pot shed’ (in fact, the work is done at the Archaeological Museum in Chora, Andros), and the Torone pot shed, as Olwen Tudor Jones had been (more about Olwen in Part 1).

Beatrice also took Olwen’s systematic paper documentation system and took it to the next level, slowly migrating the information from registers, inventory cards and notebooks of both excavations to digital databases, and scanning the drawings, photographs and plans since 1993.

This data has been fed into Heurist, a web-based multimedia database management system developed by the University of Sydney Arts eResearch team.

(A key member of the Arts eResearch team is Andrew Wilson, an archaeologist who is also a key member of the Zagora team. As well as Beatrice, other significant contributors to the development and refinement of the Zagora/Heurist database have been Stavros Paspalas, ZAP co-director, Matt McCallum, Zagora architecture specialist, and Kristen Mann, one of the Zagora trench supervisors.)

Part of the initial impetus for the development of Zagora/Heurist was to pull together the information required for publication of the 1967-74 excavations at Zagora. The Zagora/Heurist database has been tailored and developed to incorporate not only all the artefact and excavation registers but also all the architectural plans, photos, drawings and notebooks from the original 1967-74 excavations. The database has been augmented to incorporate data from the 2012-14 excavations, so that the new discoveries both in the field and in the potshed can be understood against the background of the earlier excavations.

All this data represents thousands of hours of typed information and large volumes of scanned files. The data, coupled with the digitisation of Jim Coulton’s schematic and stone-by-stone plans into a geographic mapping database (ArcGIS), means that the usefulness and potential of Zagora/Heurist now significantly surpasses the original aims.

The complete archive is available to all researchers working on Zagora research and publications – whether in Sydney, Athens or Oslo, and all their analysis is available to each other in real time as it grows.

The aim of current University of Sydney excavations is to digitally capture the entire process on site as the excavation is taking place. This includes recording everything relevant to the site: the terrain, architecture, artefacts, seeds, bones, and even the dirt that is removed.

Information about time, date and location is logged automatically by the digital tablet device, and the archaeologist enters a textual description and photographs, enabling everything to be cross-referenced. All entries relating to a trench are linked: the photographs and text related to a particular house, area, bench, artefacts…. whatever has been excavated from that location.

Stavros and Beatrice also use digital tablets to identify and categorise the ceramics and register all the other finds.

Each set of data – from the field and from the museum – is equally important. The field data tells us about the town – building layout and density, architecture, and location of finds within trenches; the finds data (which includes ceramics, seeds, bones, slag and obsidian) tells us about the nuances of everyday life – what they were eating, storing, transporting and trading. Together, these provide a comprehensive understanding of Zagora settlement life.

Both sets of data (including text and images) are uploaded into a centralised database at the end of each working day enabling them to be linked immediately. This has only been possible with recent developments in digital databases. Before this, the data sets were stored separately and it was difficult to get a holistic view of a site and its finds.

The aim is to enable data to be cross-referenced at any time, regardless of a researcher’s focus and whether the enquiry is broad or specialist. It should enable one to answer a question about what kind of floors and pottery were found in a particular kind of house, for example, a house with a hearth and one bench.

The researcher could then narrow the search to look at every bench at Zagora – and they will show up on the plan, along with expert comments related to the benches and/or the soil composition and/or location of the benches. S/he can also query what was in the benches. (At Zagora, stone benches were built inside houses, along walls. There were often ‘nests’ (pot emplacements) built into the benches, in which large ceramic vessels were contained. Such storage preserved foodstuffs such as grains, wine or olive oil by keeping it cool due to the insulation properties of the bench.)

Access to this material in the database also enables the field archaeologists to get a much better idea of the objects they unearthed.

Before the information was in databases, researchers would have to read dozens of different notebooks and look at an array of plans and photographs, and then correlate that information. Then they’d have to cross-reference it to the inventoried finds. This could take months or even years to do. The Heurist database enables this to be done in seconds.

But there are other important benefits to using the database rather than records written on paper. Errors in data are minimised or eradicated because they are recorded directly into a digital device at the location at the time of the observation. There is no dependence on memory when archaeologists are busy or tired, trying to remember what they had observed, or possibly misdeciphering hand-written notes, and to log which photo at what time and date relates to which piece of textual information. Also, putting the text directly into the database, instead of writing it down on paper, eliminates the possibility that the paper could be lost, misplaced or blown away by the Zagora wind. It is more time efficient because the information is recorded directly, just once, into the digital device – rather than being written down, and then transcribed into a computer.

All the photographs taken in the field are also uploaded into the database which provides visual references for the textual documentation.

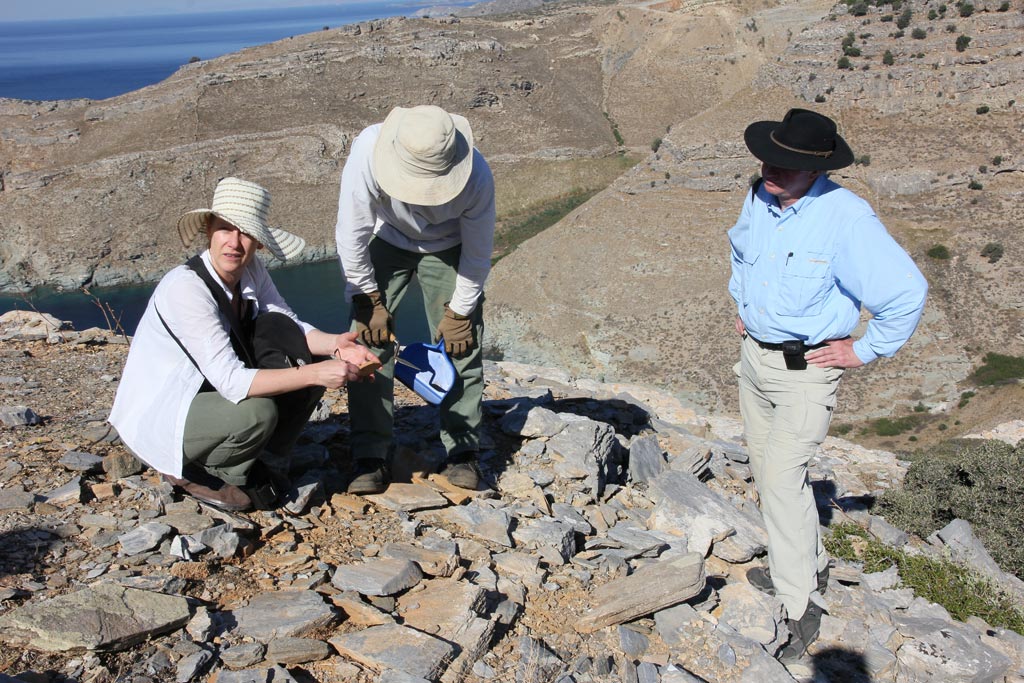

Recreation time

Here, to finish this 2-part profile of Beatrice and her work, are a couple of photos of her enjoying some recreation time with her Zagora friends and colleagues.