by Hugh Thomas

Archaeologist

A few weeks ago I was in a classroom in the University of Sydney lecturing about ancient trepanation, the process of drilling into someone’s skull to relieve pressure caused by the brain swelling, whilst they are alive and likely conscious. A few minutes before I was flashing up images of mass graves found in Athens, full of unceremoniously dumped plague victims including men, women and children. The day before I had lectured about women who had torn out their hair in mourning or had scratched large cuts into their cheeks with their nails. My name is Hugh Thomas and I study dead people!

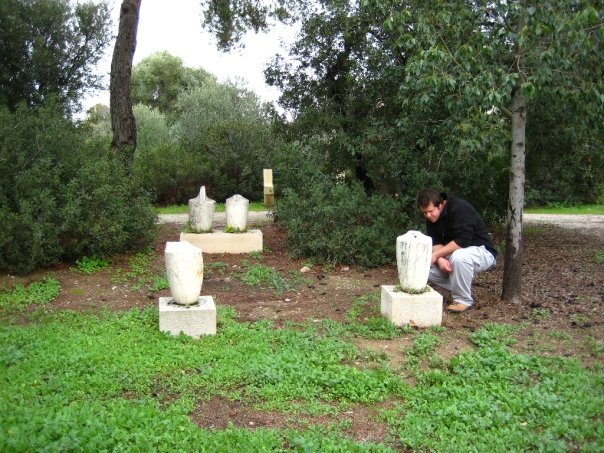

For the last six years I have been studying death in Ancient Greece. My PhD thesis has been on the images of death in Greek art. I analysed how people are depicted mourning, at what point of the mourning process they might be and looked at the various ways people commemorated the ones they had lost. So for me, my participation in the Zagora Archaeological Project is primarily focused on one area: graves.

For many archaeologists, excavating a grave is both a goal and a highlight of an archaeological career. So much of archaeology revolves around studying the material culture used by ancient peoples, such as pottery or architectural remains. However, by excavating a grave, you meet, face to face, the people you have been studying. From all accounts it is both an exciting and emotional event. You are, in effect, digging up a person who, like it or not, in the future you will join in the earth. You are excavating someone’s mother or father, their son or daughter, a person who was loved by many or by few.

You must show respect for the person and treat them how you would wish you or your loved one would want to be treated after death. At the same time, some graves are filled with beautiful grave goods such as pottery or jewellery and this can be tremendously exciting.

As much as I have studied death at an academic level and lectured university students about the topic, all the archaeological excavations I have taken part in have been based on either religious or civic buildings, such as temples or theatres. I have never had the opportunity to excavate a burial.

That is why I am excited about Zagora. Ancient settlements need a cemetery and it is my hope that we may find it. We know burials exist, not only because they have to, but also because over the last century, farmers have stumbled across two or three ancient graves near the site.

The archaeological museum of Chora, the main town on the island of Andros, has a small section dedicated to these graves, filled with beautiful Geometric pottery pulled out of the earth by someone who now themselves has probably been buried nearby.

It is my hope that through the scientific practices employed by the excavation and also through a bit of luck, we may stumble across the cemetery or at least a few graves. For me, I will not so much be excited about finding a ‘body’, but instead, I will finally witness the remains of the rituals and events that occurred at the burial.

We have written accounts of events occurring at the grave such as the ta trita, where seeds and vegetation were thrown into the grave as offerings, and it is my hope there may be traces of this at the grave. The graves could help me confirm theories I have come up with about Greek burials, or alternatively, they may disprove them. We may even find traces of ancient medical practices such as trepanation. For me, to excavate a grave would be the culmination of six years of study and the analysis of thousands of objects found in, around and near graves.

I just hope we find them.