After six incredible weeks the 2024 Zagora Archaeological Project field season is coming to a conclusion this weekend as we prepare to say farewell to our second group of students and to many of our field specialists.

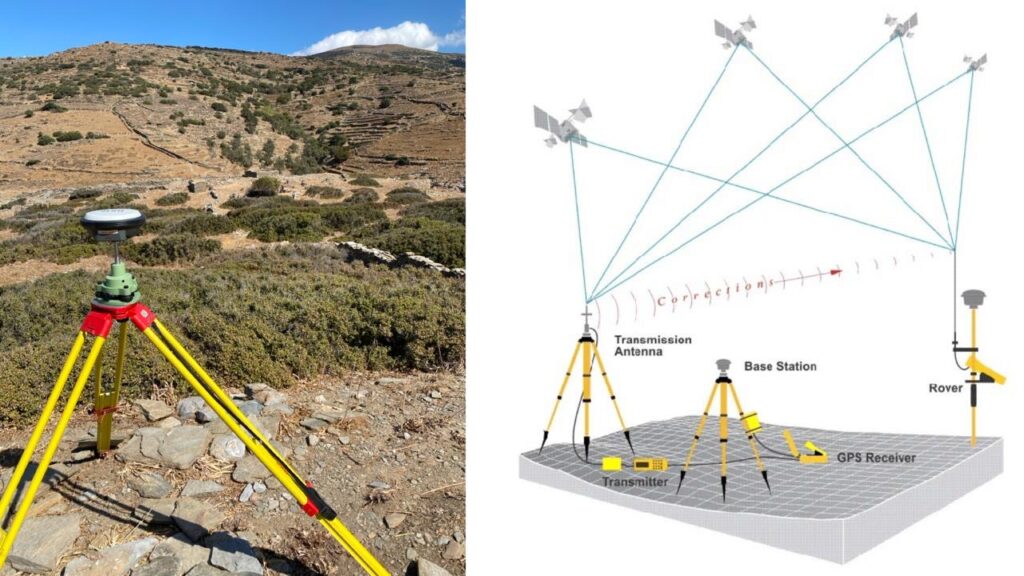

In addition to the field school the Project had a number of aims for this season, particularly exploring a possible ancient ‘industrial’ zone near the fortification wall, expanding trenches from the 2019 season, and exploring and surveying areas of the hinterland. We made use of drone technology this season to map and model the site and the results of our work, completed surface survey of selected areas of the hinterland, and updated GIS plans of the site with our new discoveries.

The past few days were dedicated to recording and backfilling all our excavated trenches this field season in order to protect and preserve the archaeology for future research and from deterioration by the elements and wandering sheep and goats. The task of backfilling the excavated trenches is physically demanding and requires all available hands working together as an efficient team. The students of the second part of the season proved to be more than up to the challenge, completing backfilling and cleaning the site ahead of schedule.

This has been another wonderful group of students who have come a long way as budding field archaeologists from their first day on site. As with the first group, students have experienced using large and small tools and to identify changes in stratigraphy. They have also learnt how to open new trenches, and how to record and document the work and the finds made, all while moving tons of earth and stone. And not least of all they have learned the art of cleaning trenches and stone in preparation for final photos and photogrammetry, all while dealing with extremely windy conditions for most their time on site.

We thank them for all their hard work and positive attitude and their interactions with the many visitors we have received on site. We wish them success in the future and kalo taxidi!